Three days before the Abu Mansur and Al Bilad dams collapsed in Wadi Derna, Libya, on the night of Sept. 10, the poet Mustafa al-Trabelsi participated in a discussion at the Derna House of Culture about the neglect of basic infrastructure in his city.

At the meeting, al-Trabelsi warned about the poor condition of the dams. As he wrote on Facebook that same day, over the past decade his beloved city has been “exposed to whipping and bombing, and then it was enclosed by a wall that had no door, leaving it shrouded in fear and depression.”

Then, Storm Daniel picked up off the Mediterranean coast, dragged itself into Libya, and broke the dams. CCTV camera footage in the city’s Maghar neighbourhood showed the rapid advance of the floodwaters, powerful enough to destroy buildings and crush lives.

A reported 70 percent of infrastructure and 95 percent of educational institutions have been damaged in the flood-affected areas. As of Wednesday, an estimated 4,000 to 11,000 people have died in the flood — among them the poet Mustafa al-Trabelsi, whose warnings over the years went unheeded — and another 10,000 are missing.

Hisham Chkiouat, the aviation minister of Libya’s Government of National Stability (based in Sirte), visited Derna in the wake of the flood and told the BBC, “I was shocked by what I saw. It’s like a tsunami. A massive neighbourhood has been destroyed. There is a large number of victims, which is increasing each hour.”

The Mediterranean Sea ate up this ancient city with roots in the Hellenistic period (326 BCE to 30 BCE). Hussein Swaydan, head of Derna’s Roads and Bridges Authority, said that the total area with “severe damage” amounts to 3 million square metres. “The situation in this city,” he said, “is more than catastrophic.”

Dr. Margaret Harris of the World Health Organisation (WHO) said that the flood was of “epic proportions.” “There’s not been a storm like this in the region in living memory,” she said. “So it’s a great shock.”

Howls of anguish across Libya morphed into anger at the devastation, which are now developing into demands for an investigation.

But who will conduct this investigation: the Tripoli-based Government of National Unity, headed by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh and officially recognised by the United Nations (UN), or the Government of National Stability, headed by Prime Minister Osama Hamada in Sirte?

These two rival governments — which have been at war with each other for many years — have paralysed the politics of the country, whose state institutions were fatally damaged by North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) bombardment in 2011.

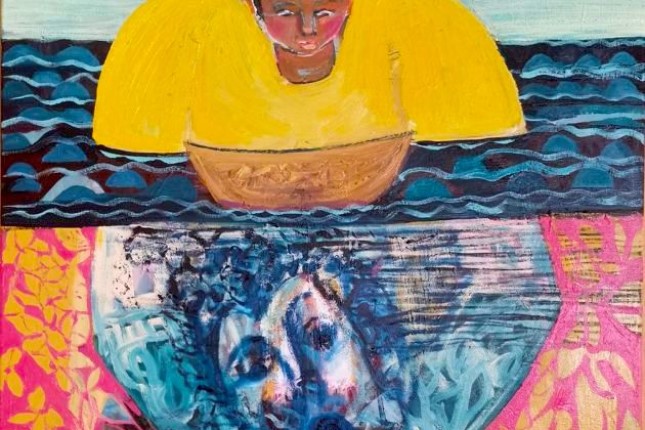

Soad Abdel Rassoul, Egypt, “My Last Meal,” 2019.

The divided state and its damaged institutions have been unable to properly provide for Libya’s population of nearly 7 million in the oil-rich but now totally devastated country.

Before the recent tragedy, the U.N. was already providing humanitarian aid for at least 300,000 Libyans, but, as a consequence of the floods, they estimate that at least 884,000 more people will require assistance. This number is certain to rise to at least 1.8 million.

The WHO’s Dr. Harris reports that some hospitals have been “wiped out” and that vital medical supplies, including trauma kits and body bags, are needed. “The humanitarian needs are huge and much more beyond the abilities of the Libyan Red Crescent, and even beyond the abilities of the government,” said Tamar Ramadan, head of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies delegation in Libya.

The emphasis on the state’s limitations is not to be minimised. Similarly, the World Meteorological Organisation’s Secretary-General Petteri Taalas pointed out that although there was an unprecedented level of rainfall (414.1 mm in 24 hours, as recorded by one station), the collapse of state institutions contributed to the catastrophe.

Taalas observed that Libya’s National Meteorological Centre has “major gaps in its observing systems. Its IT systems are not functioning well and there are chronic staff shortages. The National Meteorological Centre is trying to function, but its ability to do so is limited. The entire chain of disaster management and governance is disrupted.” Furthermore, he said, “[t]he fragmentation of the country’s disaster management and disaster response mechanisms, as well as deteriorating infrastructure, exacerbated the enormity of the challenges. The political situation is a driver of risk.”

Faiza Ramadan, Libya, “The Meeting,” 2011.

Abdel Moneim al-Arfi, a member of the Libyan Parliament (in the eastern section), joined his fellow lawmakers to call for an investigation into the causes of the disaster.

In his statement, al-Arfi pointed to underlying problems with the post-2011 Libyan political class. In 2010, the year before the NATO war, the Libyan government had allocated money towards restoring the Wadi Derna dams (both built between 1973 and 1977). This project was supposed to be completed by a Turkish company, but the company left the country during the war.

The project was never completed, and the money allocated for it vanished. According to al-Arfi, in 2020 engineers recommended that the dams be restored since they were no longer able to manage normal rainfall, but these recommendations were shelved. Money continued to disappear, and the work was simply not carried out.

Impunity has defined Libya since the overthrow of the regime led by Muammar al-Gaddafi (1942–2011). In February–March 2011, newspapers from Gulf Arab states began to claim that the Libyan government’s forces were committing genocide against the people of Libya.

The United Nations Security Council passed two resolutions: resolution 1970 (February 2011) to condemn the violence and establish an arms embargo on the country and resolution 1973 (March 2011) to allow member states to act “under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter,” which would enable armed forces to establish a ceasefire and find a solution to the crisis.

Led by France and the United States, NATO prevented an African Union delegation from following up on these resolutions and holding peace talks with all the parties in Libya.

Western countries also ignored the meeting with five African heads of state in Addis Ababa in March 2011 where al-Gaddafi agreed to the ceasefire, a proposal he repeated during an African Union delegation to Tripoli in April.

This was an unnecessary war that Western and Gulf Arab states used to wreak vengeance upon al-Gaddafi. The ghastly conflict turned Libya, which was ranked 53rd out of 169 countries on the 2010 Human Development Index (the highest ranking on the African continent), into a country marked by poor indicators of human development that is now significantly lower on any such list.

Tewa Barnosa, Libya, “War Love,” 2016.

Instead of allowing an African Union-led peace plan to take place, NATO began a bombardment of 9,600 strikes on Libyan targets, with special emphasis on state institutions. Later, when the UN asked NATO to account for the damage it had done, NATO’s legal advisor Peter Olson wrote that there was no need for an investigation, since “NATO did not deliberately target civilians and did not commit war crimes in Libya.”

There was no interest in the wilful destruction of crucial Libyan state infrastructure, which has never been rebuilt and whose absence is key to understanding the carnage in Derna.

NATO’s destruction of Libya set in motion a chain of events: the collapse of the Libyan state; the civil war, which continues to this day; the dispersal of Islamic radicals across northern Africa and into the Sahel region, whose decade-long destabilisation has resulted in a series of coups from Burkina Faso to Niger.

This has subsequently created new migration routes toward Europe and led to the deaths of migrants in both the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea as well as an unprecedented scale of human trafficking operations in the region. Add to this list of dangers not only the deaths in Derna, and certainly the deaths from Storm Daniel, but also casualties of a war from which the Libyan people have never recovered.

Najla Shawkat Fitouri, Libya, “Sea Wounded,” 2021.

Just before the flood in Libya, an earthquake struck neighbouring Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains, wiping out villages such as Tenzirt and killing about 3,000 people. “I won’t help the earthquake,” wrote the Moroccan poet Ahmad Barakat (1960–1994); “I will always carry in my mouth the dust that destroyed the world.” It is as if tragedy decided to take titanic steps along the southern rim of the Mediterranean Sea last week.

A tragic mood settled deep within the poet Mustafa al-Trabelsi. On Sept. 10, before being swept away by the flood waves, he wrote, “[w]e have only one another in this difficult situation. Let’s stand together until we drown.”

But that mood was intercut with other feelings: frustration with the “twin Libyan fabric,” in his words, with one government in Tripoli and the other in Sirte; the divided populace; and the political detritus of an ongoing war over the broken body of the Libyan state.

“Who said that Libya is not one?” Al-Trabelsi lamented. Writing as the waters rose, Al-Trabelsi left behind a poem that is being read by refugees from his city and Libyans across the country, reminding them that the tragedy is not everything, that the goodness of people who come to each other’s aid is the “promise of help,” the hope of the future.

The rain

Exposes the drenched streets,

the cheating contractor,

and the failed state.

It washes everything,

bird wings

and cats’ fur.

Reminds the poor

of their fragile roofs

and ragged clothes.

It awakens the valleys,

shakes off their yawning dust

and dry crusts.

The rain

a sign of goodness,

a promise of help,

an alarm bell.

Main photo: Shefa Salem al-Baraesi, Libya, “Drown on Dry Land,” 2019.

Source: Consortium News.