For much of the world, Afghanistan is synonymous with 9/11, Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban, suicide bombings, IEDs and the long American war. But for Indians, the story begins long before that.

The ties — historical, cultural, emotional — run deep. The ancient Silk Road connected India and Afghanistan for centuries. Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, came from Afghanistan.

For Indians, whose land had been forced into colonisation, Afghanistan’s enduring resistance to foreign rule — be it British, Russian or American — has always been compelling.

Then, there was Kabuliwala (the man from Kabul), Rabindranath Tagore’s short story of a dry fruits seller from Kabul, Abdul Rahman, who arrives in 19th-century Calcutta and forms a gentle fatherly bond with a little girl.

The 1960s Hindi film adaptation and its iconic song, Aye Mere Pyaare Watan, sung by the Kabuliwala about the pain of being far away from home captured the nation’s heart and imagination.

There has been a steady flow of Afghan refugees coming to India. Afghan students pursue higher education at Indian universities, and Bollywood music remains hugely popular among Afghans. Even amid the current wave of heightened Islamophobia in India, Afghan refugees have generally remained unaffected.

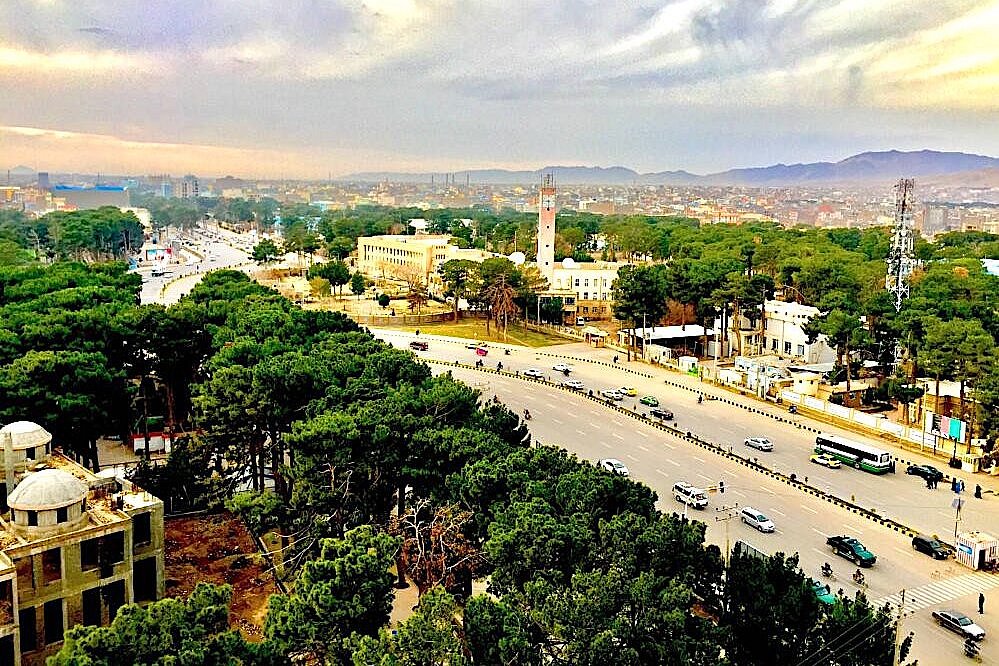

When I visited Afghanistan in 2013, I used to get this question a lot: are you Indian or Pakistani? When I said ‘Indian,’ the stiffness of the Afghans would evaporate, and they would immediately show me the Bollywood songs they had on their phones.

At the time, many Afghans were tired of what they saw as Pakistan’s interference in their country, turning Afghanistan into a hub for militant and terrorist activity after the Pakistan and U.S.-backed Mujahideen’s victory over the Soviets.

But Afghanistan still wasn’t safe for Indians. The very reasons ordinary Afghans felt warmly towards India made the Taliban wary of New Delhi’s growing influence and repeatedly targeted its embassy and consulates.

Afghanistan was once home to small but thriving Hindu and Sikh minority communities, who were successful as businessmen and traders and active members of society. But many of them left over the turbulent decades, especially under the Taliban, when Hindus were ordered to identify themselves by wearing yellow markings on their foreheads or a red cloth.

In the years after the 2002 U.S. invasion and the displacement of the Taliban, India invested nearly $3 billion in humanitarian assistance and infrastructure development — constructing a dam, highways, power transmission lines, and the Parliament building — along with projects in health, education, irrigation, and agriculture, and the construction of schools and hospitals.

This was in stark contrast to the situation two decades earlier, when India virtually had no diplomatic contact with the first Taliban regime — a government infamous for its brutal restrictions on women, public executions in football stadiums, the destruction of the priceless Bamiyan Buddhas and for turning Afghan territory into a hinterland for Pakistan’s military and intelligence project of Islamist radicalisation and terrorist training.

In 1999, India faced one of its most traumatic terror incidents when Pakistani terrorists hijacked Indian Airlines Flight 814 with 190 passengers on board, eventually forcing it to land in Kandahar.

With little leverage and the Taliban controlling the area, India was forced to release three high-profile terrorists in exchange for the hostages. The Taliban then allowed them safe passage to Pakistan, and they went on to mastermind further attacks.

Two of the three released were Masood Azhar, who then founded Jaish-e-Mohammed, a Pakistan-based terrorist group, which has carried out the most deadly attacks in India; and Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who orchestrated the kidnapping of U.S. journalist Daniel Pearl in January 2002.

A New Day

In an unexpected realignment that few could have imagined 30 years ago, India is cautiously engaging with the Taliban while Pakistan and Afghanistan are in a seriously tense situation, exchanging artillery fire and airstrikes along their border.

To counter Pakistan’s footprint in Afghanistan, India is prioritising strategic interests over the regime’s brutal oppression of women.

Last month, many Indians were stunned to see Afghanistan’s foreign minister show up in India. The complexities of the relationship became instantly clear when his first press conference was attended exclusively by male journalists.

Horrified that the Indian government had allowed this, and worried it would set a dangerous precedent, India’s women journalists pushed back, forcing a second press conference with Amir Khan Muttaqi in the Afghan embassy in Delhi.

This time, they sat in the front row, a historic sight at a time when women have been erased from public space in Afghanistan.

Muttaqi claimed that 2.8 million girls are enrolled in schools in Afghanistan, even as his regime bars girls and young women from attending secondary and higher education.

According to UNICEF, 3.7 million children aged 7-17 in Afghanistan are out of school, 60 percent or 2.2 million of them are girls. If the ban continues until 2030, over four million girls will have been deprived of education beyond primary school.

Muttaqi’s visit saw India upgrade its Kabul mission to a full embassy and create a new trade committee to deepen economic engagement. The Afghan foreign minister encouraged Indian investment in Afghanistan’s mineral, infrastructure, and energy sectors and he pledged that Afghan soil would not be used by anti-India militants, while warning Pakistan against destabilising cross-border moves.

Alhaj Nooruddin Azizi, the Taliban government’s commerce minister, then visited New Delhi for a five-day official visit that ended last Sunday, five weeks after Muttaqi’s visit. The aim was to deepen bilateral trade ties.

As the trip was ending, another deadly cycle of cross-border violence flared once again along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border.

A suicide attack this month in Peshawar, blamed by Pakistan on Afghan-based actors, killed three security personnel on Monday. This was followed by an airstrike in Khost that the Afghan government says killed nine children and a woman.

Relations between the two countries have soured since the Taliban returned to power in 2021, with each accusing the other of harbouring militant groups that carry out attacks and violate sovereignty. Rising tensions culminated in deadly border clashes in October, leaving people dead on both sides.

For decades, India–Pakistan cricket matches were battlegrounds where national pride and geopolitical rivalry spilt onto the pitch. But now, Afghanistan-Pakistan contests are also tense, most notably during the 2022 Asia Cup when there were aggressive on-field exchanges between the players and clashes between fans.

During his visit to India, Azizi, the commerce minister, made several recommendations to improve Afghan-India trade: establishing dry ports in the vast Nimroz province in southwest Afghanistan to improve trade logistics and ease cargo processing; offering a five-year tax exemption for new Indian industries, very low import duty on raw materials and machinery, and setting up Indian spice production factories and pharmaceutical investment in Afghanistan.

But perhaps the most significant recommendation was proposing the use of Iran’s Chabahar Port on the Oman Sea, which would allow landlocked Afghanistan access to the sea while bypassing Pakistan.

It would dramatically reduce Afghanistan’s reliance on Pakistan’s ports in Karachi and Gwadar for imports and exports and would give India and Afghanistan a direct connection. Though owned by Iran, India has run the port since 2018.

Sunni Taliban and Shia Iran have had a fraught relationship, so a suggestion to rely on the Chabahar Port signals a shift from sectarian alignment to economic pragmatism for both sides.

India has long practised realpolitik, placing strategic, economic, and security interests above human rights concerns. Now, with Afghanistan, it faces the moral dilemma of engaging a regime that has systematically denied women education, mobility, and basic dignity.

So far, the country shows few qualms. Media coverage has been largely celebratory rather than critical, and public opinion appears indifferent, mainly focused on one-upping Pakistan and safeguarding national security.

Source: Consortium News.