Venezuela’s escalation of its claim to Guyana’s Essequibo region has thrown the Caribbean region into a state of flux, with many observers talking of the potential for a war between the two nations that could escalate with the potential involvement of the US, UK and Brazil. The geopolitical implications, from an energy security perspective, of the fate of billions of barrels of oil reserves cannot be understated. Understanding the roots of this crisis is paramount in finding a potential solution. Some observers point to history, others to domestic Venezuelan politics. A third factor — the world’s transition away from a US-led order — should also be included.

As if from nowhere, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro recently resurrected a centuries-old dispute with neighboring Guyana over ownership of the Essequibo region, a 159,500 square kilometer territory rich in oil and minerals that has been governed by Guyana since 1864, when it was a British colony. On Dec. 3, the Venezuelan government conducted a nationwide referendum where Venezuelans were asked whether to support incorporating Essequibo as a Venezuelan state, grant citizenship to its residents and reject the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the dispute. This referendum came on the heels of weeks of campaigning by Maduro, who suddenly decided to make the Essequibo dispute a major domestic political issue and, by extension, an international crisis. The Venezuelan government claims that more than 10.5 million citizens, representing just over half of the 20.6 million eligible voters, participated in the election, and that 98% of those who participated voted in favor of the resolution.

Immediately following the referendum, Maduro swiftly ordered state oil company Petroleos de Venezuela to issue licenses for extracting oil in Essequibo, while simultaneously directing foreign oil companies working under concessions issued by Guyana to halt operations within three months. Guyana’s President Irfaan Ali responded by putting his military on alert and reaching out to allies and regional partners to activate defense agreements to protect Essequibo, which comprises two-thirds of the country and is home to 150,000 of Guyana’s more than 800,000 population. The US, which immediately declared that it would support Guyana in the dispute, began flying military reconnaissance flights over the disputed territory. Other nations, including neighboring Brazil and the UK, also weighed in on Guyana’s side.

In an effort to resolve the dispute peacefully, Maduro and Ali met on Dec. 14, where they agreed to a joint declaration where both countries agreed to “not threaten or use force against one another in any circumstances” and “refrain, whether by words or deeds, from escalating any conflict or disagreement arising from any controversy between them.” The declaration affirmed both Guyana’s position that the dispute should be resolved by the ICJ, and Venezuela’s refusal to recognize the jurisdiction of the ICJ. The two nations will continue to engage in discussions, and have agreed to meet again in three months to take stock of any progress toward resolution.

The Back Story

Venezuela maintains Essequibo was within its boundaries during the Spanish colonial period, which ended when Venezuela declared its independence in 1811. Contemporary Venezuelan maps reflect this. In 1841, following the British purchase of Guyana from the Netherlands, a British expedition dispatched to fix the boundaries of its newly acquired territory set the western boundary of Guyana at the Orinoco River, in what became known as the “Schomburgk Line” — named after Robert Hermann Schomburgk, who led the expedition. Venezuela rejected the British claim, leading to increased tensions between the two nations that ultimately led to international arbitration resulting in the Paris Arbitral Award of 1899, which awarded Essequibo to the British.

Venezuela, which was not permitted to represent itself at the arbitration (the US stood in), rejected the arbitration decision. In 1962, Venezuela referred the matter to the UN, leading to the Geneva Agreement, signed by the UK, Venezuela and British Guyana in 1966. This agreement, which Venezuela maintains nullifies the 1899 arbitration, requires the parties to seek “a practical, peaceful, and satisfactory solution to the dispute.”

There the matter rested, with neither side making progress in bilateral negotiations, until 2015, when Exxon Mobil discovered a large oil field off the coast of Essequibo. With billions of barrels of oil reserves at stake, Guyana referred the territorial dispute to the secretary general of the UN in 2018, who in turn referred the dispute to the ICJ for resolution, in keeping with the terms of the 1966 Geneva Agreement, which mandates that the issue be referred to an “appropriate international organ” in the event of a deadlock in negotiations. In 2020, the ICJ agreed to take the matter under its review.

Venezuela’s decision to hold a referendum on the status of Essequibo is designed in part to create a new set of facts before the ICJ, whose jurisdiction Venezuela rejects. As a result of the Venezuelan actions, direct negotiations have been initiated between Venezuela and Guyana along the lines set out in the 1966 Geneva Agreement. These negotiations, from Venezuela’s point of view, make any ICJ intervention moot, for the simple fact that their existence contradicts any notion of a stalemate. Moreover, the fact that Venezuela conducted a referendum further muddies the waters, invoking as it does the fundamental notion set out in the UN Charter regarding self-determination.

The bottom line is that roots of the Essequibo crisis run deep and involve far more than the simplistic analysis offered by many Western observers, which center on political opportunism by Maduro to play the nationalism card to attract votes in the upcoming presidential election. Opposition leader Maria Corina Machado’s impressive showing in the recent opposition primary has caught the attention of political observers. But the question of “why now” is driven as much by the potential for an ICJ ruling as it is by any need by Maduro to create a domestic political foil to counter a potential strong challenge by Machado.

The Geopolitical Dimension

There is another dimension, however, that cannot be ignored. In 2019, the US’ Rand Corp. think tank published a report entitled Overextending and Unbalancing Russia, in which it explored the viability of “cost-imposing options” designed to “unbalance and overextend Russia” by placing “new burdens on Russia, ideally heavier burdens than would be imposed on the US for pursuing those options.” Some observers claim that much of what is happening in the world today, from Ukraine to the Middle East, Africa and the Pacific, can be traced to policies targeting the “cost-imposing options” suggested by Rand — and pushback to these policies by certain countries.

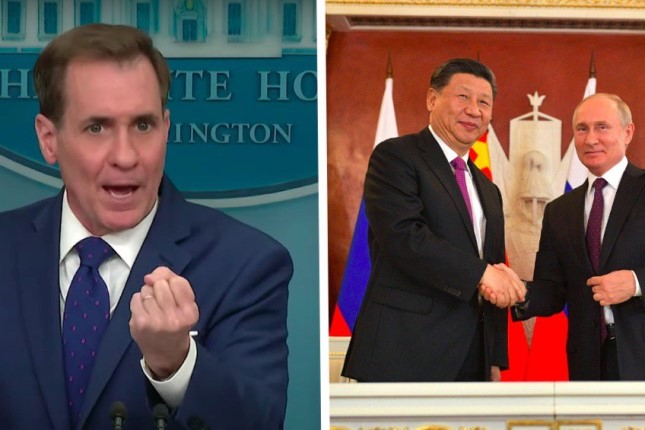

Venezuela is Russia’s most important partner in Latin America. The two have strong trade and military relations, and a shared geopolitical vision of the world. Since 2019, when the US began backing Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guido in a bid to remove Maduro from office, Russia has consistently backed Venezuela politically and materially.

Seen in this light, Venezuela’s escalation in Essequibo can be seen as part of an overall pushback by some nations to the US-led, rules-based international order. In doing so, they aim to flip the script and impose a heavier burden on the US and its allies. This is not a deliberate or cohesive agreement by nations opposed to Washington and its allies, but rather a natural reaction to US policies. As such, the world can expect more Essequibo-type crises as the US struggles to keep pace with a world that increasingly challenges the continuation of a US-led order.

Source: Energy Intelligence.