The United Nations Office of Counterterrorism says it is growing its offices overseas to become more efficient, but some civil society experts who follow the U.N.’s counterterrorism work closely remain skeptical.

They contend that the new centers expand a somewhat-secretive bureaucracy whose ambitions to battle terrorism do not adhere fully to the human rights obligations enshrined in the U.N. Charter and call the UNOTC’s work “bluewashing,” or obscuring controversial actions while operating under the blue flag of the U.N.

A top UNOTC official heartily disagrees.

The office opened its newest program hub in June in Madrid, one of 11 worldwide.

U.N. Undersecretary-General Vladimir Voronkov, who oversees the counterterrorism office, based in New York City, attended the ceremony with Spain’s Minister of the Interior Fernando Grande-Marlaska.

The Madrid center will provide technical advice and capacity-building projects for both the targets and victims of terrorism and goals to prevent violent extremism. Aiming to serve “countries from around the world,” the office ensures that it will fulfill its mandate to fight terrorism while “promoting and protecting human rights.”

Although the UNOCT deputy undersecretary-general, Raffi Gregorian, says it is not unusual for U.N. agencies to open offices outside the New York City headquarters to reduce expenses, as local hubs can be cheaper to run than operations at the U.N.’s base, counterterrorism experts from civil society organizations say they can’t identify a clear rationale for the 11 program offices. They also point to what they consider other problems with the UNOCT, including a weak focus on gender — of which Gregorian said the office was just beginning to operate — and not enough transparency.

“It’s kind of on us to get more of the word out,” Gregorian said of the activities and accomplishments of the UNOCT, which opened six years ago. He spoke to PassBlue in an interview from his office on the 37th floor of the U.N. in late June, immediately after the UNOCT held a large biennial conference at headquarters.

Before joining the UNOCT in 2019, Gregorian held numerous positions in the United States government, including as director of multilateral affairs with the Bureau of Counterterrorism of the Department of State and as director of the Office of Peace Operations, Sanctions and Counterterrorism at the State Department, from 2012-2015.

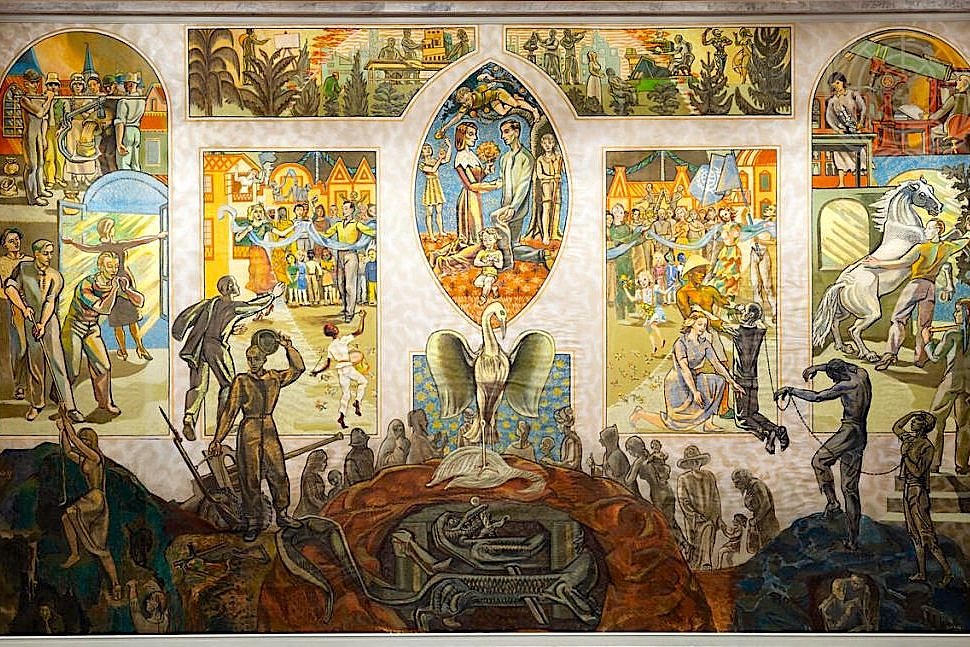

"Enhancing National, Regional & International Efforts"

Vladimir Voronkov, under-secretary-general of the UNOCT at a U.N. conference of counter-terrorism agencies on June 19. Photo: UN Photo / Manuel Elías.

The Madrid center follows UNOCT’s mandate to help coordinate participation in the organization’s counterterrorism strategy, as defined by the General Assembly, in 2006, to “enhance national, regional and international efforts to counter terrorism.”

Voronkov, a former Russian career diplomat, was expected to be reappointed to the UNOCT post in June, after six years in the job, although a U.N. spokesperson would not confirm if that happened.

Under Voronkov’s leadership, the office has established 15 programs globally. He has also aimed to improve transparency of the organization by publishing a newsletter and holding quarterly briefings to member states, according to a statement he made in 2021.

Meanwhile, U.N. member states are increasing their counterterrorism investments, spending tens of millions of dollars in the UNOCT annually and aiming to unify efforts to contain terrorist threats across the world. The office regularly holds conferences to raise awareness and share information among countries about their counterterrorism work.

In June, the UNOCT’s major biennial gathering covered topics ranging from multilateralism and institutional cooperation to the respect of human rights and rule of law in counterterrorism. It attracted hundreds of experts, civil society members and national representatives and produced a review of the office’s strategies.

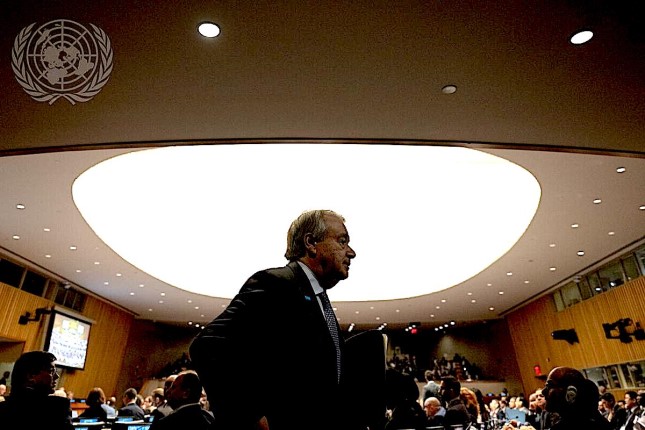

At the forum, Secretary-General António Guterres and the UNOCT pledged to improve the integration of human rights and gender considerations into the strategy and to establish a “results framework” to better monitor, analyze and communicate the usefulness of its programs to fellow U.N. member states and the public.

Guterres at the U.N. conference for counter-terrorism agencies on June 19. Photo: UN Photo / Manuel Elías.

Part of the complication in assessing the U.N.’s counterterrorism work overall is that there still is no universal, legally bound definition of terrorism — a problem that Voronkov has described as a “fact of life.” Indeed, it’s a problem that lies far outside the scope of the UNOCT.

“There remains extraordinary leeway for arbitrary and unjustified action [by states] using purported counter-terrorism as a pretext,” said Fionnuala Ni Aolain, the special rapporteur on human rights and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, at a U.N. Security Council meeting on counterterrorism in October 2022.

Such “bluewashing” actions include crackdowns on civil society groups, rounding up and threatening dissidents and quashing civil unrest or unwanted religious groups, LGBTQ+ communities and women, she noted in a March 2023 report to the Human Rights Council.

Overreach Cited in Tajikistan in 2022

Tajikistan’s Foreign Minister Sirodjiddin Muhriddin at the U.N. in 2019, addressing the need to maintain international security . Photo: UN Photo / Manuel Elías.

One recent example of possible overreach by countries battling terrorism was highlighted in July by the office of the U.N. high commissioner for human rights. Its website published a press release condemning Tajikistan for arresting and imprisoning nine representatives of civil society, including journalists, bloggers and lawyers, representing the minority Pamiri culture.

The detainees were reportedly covering “social issues and alleged human rights abuses,” the website said, when they were arrested by Tajikistani officials in May 2022. They each face sentences of up to 29 years of prison. According to the press release, experts say that “eight out of nine were allegedly accused of extremism and terrorism-related offenses,” an example of the “apparent use of anti-terrorism legislation to silence critical voices.”

The Global Center on Cooperative Security, a nongovernmental organization in Washington, produces “Blue Sky” reports, a series providing an independent overview of U.N. counterterrorism efforts. Its most recent study contains numerous criticisms of the UNOCT, including an assertion that it does not have a reliable way to measure the value of its programs. The report points out: “The United Nations lacks an effective system to monitor and hold member states accountable for human rights abuses carried out in the name of countering terrorism. Even efforts to improve the frequency and consistency of public reporting on abuses have floundered.”

Without improving the transparency and oversight of the UNOCT, it added, countries will continue to use “the guise” of counterterrorism to “employ arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, systematic use of torture against people suspected of terrorism, detention in unofficial facilities, violation of fair trial guarantees, admission of confessions obtained under duress, and violations of the rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association.”

Yet Gregorian told PassBlue there was no evidence to support contentions that “the creation of this office prompted member state ‘X’ to arrest this person or beat that person up,” he said, adding that autocratic or nondemocratic countries were exploiting international counterterrorism policies before the UNOCT’s inception.

He acknowledged, however, some of the fault-finding of the UNOCT by outsiders, though he said that the critics could contact him directly to discuss the office’s work if they wanted to and that “a lot of people write about us but never bother to call us.”

As to the usefulness of UNOCT’s programs, Gregorian said that each had its own external evaluation structure that kicks in when its specific budget reaches a certain amount. He also reiterated that the UNOCT is creating a “results framework” to evaluate its strategy.

Besides relying on the Blue Sky report to clarify the work of the UNOCT, PassBlue spoke to six experts who work in the rather tight civil society world of counterterrorism specialists, but most of the people PassBlue interviewed insisted on anonymity for fear of jeopardizing their professional relationships with the U.N.

The UNOCT’s expanding network of liaison and research offices, as in Madrid, has been steady since the UNOCT opened six years ago. But experts contend there is little transparency about the centers and their costs. Gregorian countered that the website clarifies its operations.

It mostly features press releases announcing the program offices’ inaugurations. In certain cases, a general description of each program’s work is available, sometimes accompanied by a portfolio of the personnel. For more details, however, PassBlue had to ask the UNOCT spokesperson.

Another issue for the UNOTC, experts say, is its heavy reliance on voluntary contributions from U.N. member states. Its constant need for extrabudgetary funding can also contribute to lack of transparency, critics note, fostering a pay-to-play arrangement that can undermine openness or drive a specific agenda of a country to fight terrorism.

The dynamic of relying on voluntary contributions is not unusual for U.N. agencies, commissions and programs, but it can put an entity’s independence at stake. Observers of the U.N. and even member states have long acknowledged that it is not an optimal situation. The counterterrorism office is susceptible to this process as well, numerous experts said.

Funding Issue

Qatari counter-terrorism official Nasser bin Saeed Al-Fheed Al-Hajri addressing U.N. conference of counter-terrorism agencies on June 19. Photo: UN Photo / Manuel Elías.

The office is funded voluntarily by 36 nations, with a total of $357.4 million contributed between 2009-2022. Qatar ($137.8 million) and Saudi Arabia ($110.3 million) have provided 40 percent and 32 percent of the budget, respectively. Other donors include the United States, European countries, Japan, Russia and India.

The fourth-largest contribution to the UNOCT Trust Fund comes from the U.N. Peace and Development Trust Fund, which was established in 2016 with a contribution of $200 million from China over 10 years.

The large contributions from Saudi Arabia and Qatar, experts note, suggest that the countries could have undue influence over the UNOCT and question whether human rights and respect for gender issues are being undermined by these donors, given their own dubious records on these topics.

Of the 25 UNOCT positions converted to the U.N.’s regular budget in 2023, only five are assigned to the two new human rights and gender sections. Three are general service positions, which are mostly administrative, according to the Blue Sky report.

While the mandate supporting UNOCT’s operations emphasizes the link between counterterrorism and human rights, one civil society expert told PassBlue that Saudi Arabia’s involvement in fighting terrorism has pushed a shift to “hard security” programs, such as border control, cybersecurity and data collection, like the Counterterrorism Travel Program (CTTP), which Gregorian has worked on since his days at the U.S. State Department and is considered one of the most popular endeavors of UNOCT.

The role of the office’s overseas centers include conducting research and coordinating with local governments to carry out counterterrorism goals.

Travel Section

Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport. Photo: Jorge Franganillo / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0.

PassBlue contacted the Budapest center, and Gregorian responded for it, telling PassBlue by email that “most of the UNOCT staff in the Budapest Programme Office work on UNOCT’s Countering Terrorist Travel Section, which manages the inter-agency Countering Terrorist Travel Programme.”

It supports 66 member states around the world, including 25 in Africa, using advanced passenger records to “track and interdict” suspected and known terrorists, as well as other criminals. The range of countries relying on the program runs from Norway to Botswana.

Gregorian told PassBlue that opening an office in Budapest was an easy decision since Hungary covers the cost of the office and equipment and that staff wages are lower than in New York City. Travel expenses for the personnel to meet with regional clients also cuts costs rather than traveling from U.N. headquarters.

“It’s much cheaper and faster to get to [countries that benefit from the CTTP] from Budapest than to get there from New York,” he said. “Someone travels [from] New York to Africa, they’re going to get business class — that’s the U.N. rule.” Hungary also provides training for the program through the International Law Enforcement Academy in Budapest, and the UNOCT center can exchange data with the U.N. Information Service office in nearby Vienna.

The UNOCT added 15 new staff positions abroad in the last two years, raising the total to 55, and it plans to expand into Iraq to support “prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration,” according to the Blue Sky report. In total, the UNOCT has 198 staff positions, 165 of which are funded by extrabudgetary donations.

The voluntary pot, called the Counterterrorism Trust Fund, has a $67.6 million budget for 2023. Voronkov spends a lot of time traveling with his colleagues to countries interested in participating in the office’s programs. The UNOCT also hires consultants and videographers to produce pitches — sometimes in the form of videos — for the services that the UNOCT can offer, an expert said.

Responding to the Blue Sky report’s focus on the perceived problem of extrabudgetary financing for the UNOTC, Gregorian said it was weaning itself off such sources of money, and that it will primarily be used for “capacity building” and technical assistance instead of policy and strategy.

The UNOCT intends to convert 24 more positions to be paid through the U.N. regular budget, Gregorian said, including “the last couple of people in the human rights and gender section.” To diversify its funding, he noted that the office needs “access to those parts of the [member state] governments, donor governments, that have funds that are legally authorized to be used for [human rights, gender, and Rule of Law] purposes.”

The Blue Sky report underlined the “chronic and systemic” relegation of human rights and gender considerations, a main pillar of the UNOCT’s mandate, as a low priority. Gregorian agreed that the UNOCT needed to “up [its] game, both in terms of the prominence and the focus, but also to help mobilize resources and awareness of what we do” regarding a gender concentration in the counterterrorism strategy.

He pointed to some progress: By using a donation from Canada, a gender unit program office was opened in January 2022, which led to the Gender and Identity Factors Platform, an information-sharing and training source for U.N. entities, civil society groups, practitioners, researchers and countries to better understand the “gender and intersectionality in countering terrorism and in preventing and countering violent extremism.”

The unit, operating from the UNOCT headquarters, is run by two gender experts and a general service staff. Part of Canada’s contribution will also be used to provide human rights training for law enforcement and intelligence people, Gregorian said.

Overall, however, “the funding doesn’t match [member state] rhetoric,” Gregorian said, notably on gender matters. Yet such a component can be a powerful tool to combat terrorists’ movements and tactics, he added, citing as examples the UNOCT’s Border Security Management and the Global Programme on Detecting, Preventing and Countering the Financing of Terrorism.

The latest review of the UNOCT counterterrorism strategy, published in July, “stresses the significance of a sustained and comprehensive approach, including through stronger efforts, where necessary, to address conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism, bearing in mind that terrorism will not be defeated by military force, law enforcement measures and intelligence operations alone.”

The bottom line is that the office is in demand. One expert who closely observes the entity and insisted on anonymity, said that “everyone wants OCT,” not only Saudi Arabia and Qatar but also Western states.

Countries benefit from the resources of the office, such as using the technology to track the activities of a terrorist, but given that there is no firm definition of a “terrorist,” means that it can be applied loosely by countries and lead to, as some people in the human rights community suggest, “bluewashing.”

Gregorian pointed out, however, that “member states are actually responsible for the strategy, not the U.N.,” referring to the original agenda agreed on by the General Assembly.

Main photo: Raffi Gregorian, UNOCT deputy undersecretary-general, in 2022 © UN Photo / Mark Garten.

Source: Consortium News.