When I joined the C.I.A. in January 1990, I did it to serve my country and to see the world. I believed at the time that we were the “good guys.” I believed that the United States was a force for good around the world. I wanted to put my degrees—in Middle Eastern studies/Islamic theology and legislative affairs/policy analysis—to good use.

Seven years after joining the C.I.A., I made a move to counterterrorism operations to stave off boredom. I still believed we were the good guys, and I wanted to help keep Americans safe. My whole world, like the worlds of all Americans, changed dramatically and permanently on Sept.11, 2001. Within months of the attacks, I found myself heading to Pakistan as the chief of C.I.A. counterterrorism operations in Pakistan.

Almost immediately, my team began capturing Al-Qaeda fighters at safehouses all around Pakistan. In late March 2002, we hit the jackpot with the capture of Abu Zubaydah and dozens of other fighters, including two who commanded Al-Qaeda’s training camps in southern Afghanistan. And by the end of the month, my Pakistani colleagues told me that the local jail, where we were temporarily holding the men we had captured, was full. They had to be moved somewhere. I called the C.I.A.’s Counterterrorism Center and said that the Pakistanis wanted our prisoners out of their jail. Where should I send them?

The response was quick. Put them on a plane and send them to Guantanamo. “Guantanamo, Cuba?” I asked. “Why in the world would we send them to Cuba?” My interlocutor explained what, at the time, sounded like it had been well thought out. “We’re going to hold them at the U.S. base in Guantanamo for two or three weeks until we can identify which federal district court they’ll be tried in. It’ll be Boston, New York, Washington, or the Eastern District of Virginia.”

That made perfect sense to me. The U.S. is a nation of laws. And the country was going to show the world what the rule of law looked like. These men, who had murdered 3,000 people on that awful day, would go on trial for their crimes. I called my contact in the U.S. Air Force, made the arrangements for the flights and loaded my handcuffed and shackled prisoners for the trip. I never saw any of them again.

The problem is that U.S. leaders, whether they were at the White House, the Justice Department or the C.I.A., never really intended any of these men to face trial in a court of law, being judged by a jury of their peers. The fix was in from the beginning.

A Plan to Legalize Torture

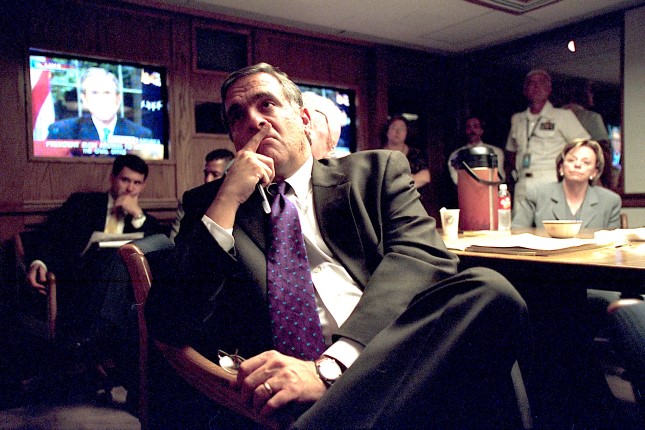

C.I.A. Director George Tenet listens to President George W. Bush’s address on Sept. 11, 2001, in the President’s Emergency Operations Center. Photo: U.S. National Archives via Flickr.

Just a month after the Sept. 11 attacks, the C.I.A. leadership gathered its army of lawyers and black ops people and came up with a plan to legalize torture. This was despite the fact that torture has long been patently illegal in the United States. But it didn’t matter. There was no thought to the long term. There was no worry about what would happen if prisoners were tortured and then actually did have to go on trial. Nothing they said would be admissible. But nobody cared.

On Aug. 2, 2002, C.I.A. officers and contractors began torturing Abu Zubaydah at a secret prison. That torture was well-documented in the Senate Torture Report, or rather, in the heavily-redacted Executive Summary of the Senate Torture Report. The report itself will likely never be released. But even in its redacted version, and with comprehensive footnotes, it paints a horrifying picture of what the C.I.A. did to its prisoners. That torture, that policy, has come back to haunt the C.I.A.

Abu Zubaydah Redacted. Photo: Jared Rodriguez / t r u t h o u t / Flickr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

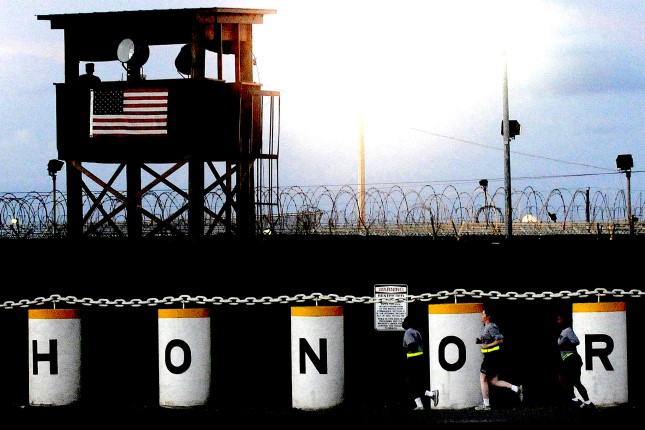

Military trials have always moved at a glacial pace at the U.S. base at Guantanamo, Cuba, where the United States has kept a total of roughly 780 prisoners from the so-called War on Terror since early 2002. That number is down to a few dozen of what the government calls the “worst of the worst.” Only a small handful are cleared for eventual release, pending the identification of a country willing to take them. The rest will likely never be released.

The problem with charging a defendant at Guantanamo has proven to be several-fold. First, much of the evidence that the Pentagon wants to use against the likes of alleged Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Shaikh Muhammad, accused Al-Qaeda facilitator Abu Zubaydah, accused Sept. 11 facilitator Ramzi bin al-Shibh and others was collected by C.I.A. officers and contractors through the use of torture. That in and of itself essentially doomed the cases from the start.

None of that information, no matter how damning it may be, can be used against them. Even the purported “worst of the worst” have constitutional protections, whether we like it or not. Second, what information that remains against each defendant is generally classified — usually at a very high level — and the C.I.A. is unwilling to declassify it, even for a trial.

Consequently, no trials progress except at the slowest possible bureaucratic pace. And if you’re the C.I.A., why would you care if trials proceed? Nobody’s going anywhere, whether they do or not.

Voluntary Confessions

The guard tower at Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp Delta in Cuba, 2010. Photo: Joint Task Force Guantanamo / Flickr / CC BY-ND 2.0.

With that said, the Pentagon is still willing to go through the motions. In 2006, the Pentagon initiated a program whereby law enforcement officers tried to get Guantanamo defendants to make voluntary confessions independent of what they had told their C.I.A. torturers. That way, the torture couldn’t be used as a defense. But that effort failed.

In 2007, a military judge threw out a confession that these officers obtained from Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a Saudi prisoner who has been accused of being the mastermind behind the USS Cole bombing, in which 17 American sailors were killed. The Pentagon argued that the officers made clear to Nashiri that his statement was completely voluntary. But the judge held that after four years in secret C.I.A. prisons, where Nashiri was tortured mercilessly, “any resistance the accused might have been inclined to put up when asked to incriminate himself was intentionally and literally beaten out of him years before.”

This is the same reason that Khalid Shaikh Muhammad, Abu Zubaydah and others have not been tried, despite having been in U.S. custody for more than 20 years. And to make matters worse, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, accused of being one of the most dangerous masterminds of the Sept. 11 attacks, last week was declared mentally unfit to stand trial. Relentless C.I.A. torture at black sites around the world and at Guantanamo, has caused “psychosis and post-traumatic stress disorder” so severe that he is not only unable to participate in his own defense, but he is so insane that he cannot even enter a plea and understand what he is doing. Defense attorneys said in court last week that the only hope of making bin al-Shibh sane enough to be tried would be to provide him with post-trauma psychological care and to release him from military confinement. That will never ever happen.

Bin al-Shibh’s attorneys say that in the four years between when he was captured by the C.I.A. in 2002 and his transfer to Guantanamo in 2006, their client “went insane as a result of what the Agency called ‘enhanced interrogation techniques,’ that included sleep deprivation, waterboarding, and beatings.” Bin al-Shibh ranted incoherently during a court hearing in 2008, and his mental state has been an issue ever since.

Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew of Khalid Shaikh Muhammad, and another accused Sept. 11 conspirator, has had a similar experience. Like his co-defendants, Baluchi, who also goes by the name Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, is facing the death penalty, if he can ever get a trial. But he, too, was the victim of C.I.A. torture. A 2008 report by the C.I.A. Inspector General, declassified and released in early 2023, found that Baluchi had been used as a “living prop” to teach C.I.A. trainee interrogators, who lined up to take turns knocking his head against a wall, leaving him with permanent brain damage. The report also said that in 2018, Baluchi was given an MRI and examined by a neuropsychologist, who found “brain abnormalities consistent with traumatic brain injury, and moderate-to-severe brain damage.” Like bin al-Shibh, Baluchi is unable to participate in his own defense.

Americans Should Know

The Torture Team, from left: Dick Cheney, John Yoo, George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld. Photo: DonkeyHotey / Flickr / CC BY-SA 2.0.

All Americans should know about these recent developments. All Americans should understand that the purpose of trials would be to expose the truth. Citizens have a right to know what happened on Sept. 11. Without that information, conspiracies run wild. Without that information, there is no accountability. Americans have a right to know about the planning for the attacks and about what Al-Qaeda did. But at the same time, Americans have a right to know what the official government response was. Why did torture suddenly become acceptable? Who was responsible for it? And why weren’t they punished for obvious crimes against humanity?

In the end, I was the only person associated with the C.I.A.’s torture program who was prosecuted and imprisoned. I never tortured anybody. But I was charged with five felonies, including three counts of espionage, for telling ABC News and The New York Times that the C.I.A. was torturing its prisoners, that torture was official U.S. government policy and that the policy had been approved by the president himself. I served 23 months in a federal prison. It was worth every minute.

There is certainly no easy fix to this situation. The New York Times reported in March 2022 that prosecutors had opened talks with attorneys representing Khalid Shaikh Muhammad and four co-defendants to negotiate a plea agreement that would drop the death penalty in exchange for sentences of life without parole and promises that the men would be allowed to remain in Guantanamo, rather than to be transferred to a Supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, where prisoners are held in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day. Defense attorneys also said the men vastly prefer the weather of eastern Cuba to the snows of Colorado. The Times notes that such a deal would infuriate death penalty advocates among the families of the victims of the Sept. 11 attacks.

I’m sure that’s true, and I’m sorry if their feelings would be hurt by such a decision. But as angry as they might be at the likes of Khalid Shaikh Muhammad, Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, and the others, they should be at least as angry with the likes of former C.I.A. Director George Tenet, former C.I.A. Deputy Director John McLaughlin, former C.I.A. Deputy Director for Operations Jose Rodriguez, former C.I.A. Executive Director John Brennan and C.I.A. contract psychologist and torture program creators James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, all of whom were the godfathers of the torture program.

They should be just as angry with the Justice Department attorneys John Yoo and Jay Bybee, who did intellectual handstands to convince themselves that the torture program was somehow legal. And let’s not forget that the buck has to stop somewhere. Blame should be cast on former President George W. Bush and former Vice President Dick Cheney. This cast of characters weakened U.S. democracy by pretending that the Constitution and the rule of law didn’t exist. Their irresponsibility, childish emotion and willingness to commit crimes against humanity guaranteed that the men who likely committed the worst ever crime against Americans will never be fully and legally punished. Future generations should know that.

Main photo: June 16, 2010: U.S. soldiers run infront of Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp Delta detention center © Joint Task Force Guantanamo / Flickr / CC BY-ND 2.0.

Source: Consortium News.