After intense pressure by the U.S. on Panama to return possession of its canal to Washington because the Trump administration thinks China is threatening it, the Central American nation on Sunday sought a compromise by announcing it would study whether or not to renew contracts with a Chinese company managing two ports on the waterway and would withdraw from China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The announcement was made by Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino after meeting with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Panama City. However, it’s not clear that the compromise, which seeks to alleviate U.S. concerns about China but does not return the canal, will work. Mulino said an audit would look into not extending the Chinese port contracts and said Panama would leave the Chinese infrastructure project BRI by 2027, if not earlier.

These move were clearly not enough to satisfy Rubio and President Donald Trump about the supposed Chinese threat to canal security. Shortly after the meeting, the State Department issued a statement threatening necessary measures unless there are “immediate changes” regarding China. The statement said: “… the current position of influence and control of the Chinese Communist Party over the Panama Canal area is a threat to the canal and represents a violation of the Treaty Concerning the Permanent Neutrality and Operation of the Panama Canal. Secretary Rubio made clear that this status quo is unacceptable and that absent immediate changes, it would require the United States to take measures necessary to protect its rights under the Treaty.”

Speaking to reporters in Maryland on Sunday, Trump said, “We’re going to take [the canal] back, or something very powerful is going to happen.”

At Sunday’s press conference after meeting Rubio, Mulino, who looked uncomfortable, told reporters, “There is no question that the canal is operated by Panama and will continue to be so. I don’t think there was any discrepancy on that. I did not feel any threat.”

Saúl Méndez, general secretary of Suntracs, the union representing many canal workers, told Consortium News in an interview that he and his members do not trust the Panamanian president. “Mulino makes a deal that meets U.S. interests but damages Panama,” he said.

Given the history of local oligarchs doing Washington’s bidding, Méndez has been organizing a series of actions to alert Panamanians to the risk of a sell-out to the United States. He and other trade unionists were out on the streets on Sunday to protest Rubio’s visit.

On the day Donald Trump was inaugurated, a large group of trade unionists gathered outside the U.S. ambassador’s Panama City residence to burn U.S. flags, protesting Trump’s declared intent to take back the canal.

Méndez said Trump’s intentions were “deluded.” Panama is a sovereign country and “a foreigner like Trump can’t come here and take something that’s not his,” he said.

Méndez said most Panamanians feel the same. Even the more sober head of the Panamanian chamber of commerce said Trump’s arguments were “unreal and invalid.”

But Méndez sees a more insidious internal threat: Panama’s own “traitors” who might act against Panama’s interests. He uses two words to describe such people: vendepatrias and gringeros.

The first means people who sell their own country; the second are Latin Americans who strongly identify with the U.S. Méndez accuses Mulino of being both.

Doing US Bidding

Mulino took office last July on a platform promising closer ties with Washington. But, given local reaction to Trump’s threat, he has been obliged to declare that the canal “is, and will continue to be, Panamanian.” However, before that Mulino had bent over backwards to do Washington’s bidding.

For the Biden adminstration, he limited the passage through Panama of U.S.-bound migrants; and when Trump was elected, he welcomed his harsh anti-immigration policies. He even hubristically advised Trump in November that “the real U.S. southern border is not with Mexico but in Darién,” Panama’s treacherous frontier with Colombia that was crossed by over 300,000 migrants last year.

Bizarrely, he said this again, in Davos, only a few days after Trump, seemingly indifferent to the solicitous Mulino, repeated his claim that the canal was wrongly ceded to Panama 25 years ago.

History of the Canal

Part of the Panama Canal. (Joe Lauria)

The history of the canal began in the late 19th century, an era which, David Sanger in The New York Times notes, “Mr. Trump keeps talking about wistfully.” It is not difficult to see why.

Author Matthew Parker, in his history of the canal, says that, under U.S. President William McKinley and later President Teddy Roosevelt, Washington cast off “its historical aversion to imperialism and aggression on the international stage” and became expansionist. To link its new colonies, it needed a shorter sea route between the oceans.

Once “the battle of the routes” was resolved in favor of Panama rather than Nicaragua, the main obstacle was that the isthmus was still part of Colombia, which refused to cede the territory required for the canal.

It took what Parker calls the “bellicosity” of Roosevelt to impose a solution. He used duplicity, bribes and a U.S. gunboat to rid the territory of Colombian troops, quickly recognizing the declaration of independence made by a group of Panamanian oligarchs.

“Go Away, Little Man, and Don’t Bother Me,” American political cartoon, c 1903, by Charles Green Bush from The New York World, of President Theodore Roosevelt intimidating Colombia to acquire the Panama Canal Zone. By Charles Green Bush – New York World. (The Granger Collection, NY, Wikipedia Commons, Public domain)

As Méndez pointed out, these early vendepatrias then signed the 1903 Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty., which Parker says “in all likelihood” they never read, even though “it was to reduce their new country to little more than a vassalage.” Roosevelt said such a conclusion “could not have been accomplished save by me or by some man of my temperament.”

Another aspect might also have impressed Trump. For nearly a century, the Canal Zone was completely controlled by the U.S. as as if it were sovereign U.S. territory. A child born there to at least one American parent became a U.S. citizen and could run for president, such as the late Sen. John McCain, who was born in the Zone.

Segregation in there was complete. Most Panamanians were barred from entry, and all housing and other facilities were allocated either to “Gold” (or white) residents or to “Silver” (non-white) residents, with huge differences in standards.

Parker gives the example that Gold schools had an average of 17 pupils per teacher, while Silver ones had 115.

Méndez also said it took years of political pressure by Panamanians, including violent protests in 1964 that left 20 dead and 500 wounded, before the canal’s handover to Panama was eventually agreed in 1977.

The Torrijos–Carter Treaties, signed by presidents Jimmy Carter and Omar Torrijos, led to the U.S. ceding control, but not until December 1999. Four years after the signing, Torrijos died in what even The New York Times called a “mysterious” plane crash.

The ceremonial transfer of the Canal Zone at Miraflores Locks on Dec. 14, 1999. (Joseph Wood, Robert “Bob” Parker, University of Florida Digital Collections, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Doubts that Panama would run the canal effectively were unfounded. A 2010 study argued that it had “thrived” under management by the government-owned Panama Canal Authority. It has become a crucial part of the country’s economy, generating 4 percent of national income.

A referendum on widening the canal in 2006, supported by 78 percent of voters, led to $5 billion being invested to allow the passage of bigger ships.

However, the U.S. undeniably continues to have a big stake in the canal. Three-quarters of ships using it are going to or coming from U.S. ports. Nearly 10,000 ships made the transit in 2024 — representing 5 percent of global trade and paying hugely varying fees that can reach $300,000 or more, according to the size of vessel.

Trump’s unfounded claim that U.S. ships pay excessive charges may have been sparked by an overall increase in fees in 2024, when the canal’s capacity was affected by drought.

Trump’s assertion that China is “operating” the canal is equally egregious. But there are five sea ports linked to the canal, operated by foreign contractors, of which two are run by Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings.

When the concessions were made to the Chinese companies in 1999, the U.S. State Department concluded it represented no risk to U.S. interests, and the Chinese government recently stated it “does not participate in the management and operation of the canal.”

Hutchison operates ports in 24 countries, including the U.K. and Germany. This hasn’t stopped China hawk Rubio questioning whether Chinese companies could take control of the ports on the orders of Beijing and “shut it down or impede our transit.”

China’s links with Panama are very important in a different sense. In recent years China has become Panama’s biggest export market, worth nearly 10 times the country’s exports to the U.S.

Panama was also the first Latin American country to sign on to China’s “Belt and Road” initiative in 2017, after it cut its ties to Taiwan. Results have been mixed so far.

Panama has been hesitant about getting closer to China, but a Chinese firm is building a new road bridge across the canal. However, Mulino, backtracking on a Chinese proposal for a new railway line to Costa Rica, has handed the contract to a U.S. firm.

Recalling 1989

Flames engulf a building following hostilities between the Panamanian Defense Force and U.S. forces during Operation Just Cause, Dec. 21, 1989. (SPEC. MORLAND, DoD, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Trump’s claim to U.S. ownership of the canal, saying that it would be restored by force if necessary, raises painful memories for Panamanians.

While last December was the 25th anniversary of the canal’s handover, it also marked 35 years since Operation “Just Cause,” the 1989 invasion of Panama by U.S. forces to abduct the then president, Manuel Noriega, a former C.I.A. asset who had shown dangerous leftist tendencies.

War correspondent Martha Gellhorn described the aftermath: thousands killed and whole barrios devastated. Panama could do little to defend itself and now, with no army, could do even less.

If Trump were instead to put financial screws on Panama’s economy, it would certainly be vulnerable. The country has no central bank, its currency is the U.S. dollar and its banking system and financial services industry are tightly linked to the U.S. The Panamanian military is also not match to U.S. armed forces.

Its vulnerability led Mulino to the concessions he made on Sunday with Rubio on possibly not renewing the port contracts and pulling out of the Belt and Road initiative, clearly not enough for Rubio and Trump, who are both obsessed enough with China to do something rash.

The rebuilt neighborhood of El Chorrillo in Panama City in 2024, which the U.S. bombed in 1989 with heavy loss of civilian life. (Joe Lauria)

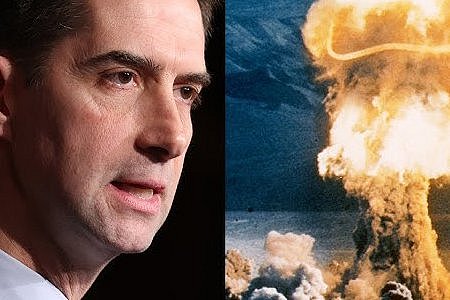

Main photo: U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio meeting Sunday with Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino in Panama City © State Department, Freddie Everett.

Source: Consortium News.