Former President Aslan Bzhania resigned in late 2024 amid civil unrest sparked by a proposed Russian-Abkhazian “investment agreement” widely perceived as a threat to Abkhazian sovereignty. Unlike other separatist territories in the former Soviet Union, Abkhazia has long sought true independence rather than integration into Russia. However, due to its lack of international recognition and reliance on Moscow for economic and security support, this goal remains elusive.

On February 18, 2025, Abkhazia held presidential elections with five candidates competing, none of which received an outright majority, leading to a March 1st runoff between acting President Badra Gunba, the Kremlin’s preferred candidate, and Adgur Ardzinba, a nationalist advocating full independence. Gunba secured 55% of the vote, while Ardzinba received 42%, with a 70% voter turnout – a sign of the election’s high stakes.

However, the election process was marred by allegations of carousel voting in Russia’s Karachay-Cherkessia Republic, intimidation of Abkhazia’s Armenian community, and even armed violence at a polling station in Tsandrypsh. In the first round, accusations of Russian interference emerged when members of the Abkhaz diaspora in Turkey, most of whom support the opposition, were detained at Russia’s Adler airport and barred from entering Abkhazia, effectively disenfranchising them. These controversies highlight the deep divisions within the country and the extent of external influence over its political process.

Gunba’s victory was swiftly endorsed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, reinforcing the perception that Moscow sees Abkhazia as a key strategic partner. Yet within Abkhazia, the divide remains stark: while many voters support full independence, others see closer ties with Russia as the only viable path to economic and political stability. Gunba has pledged to make Abkhazia “free, independent, and prosperous,” but his close Kremlin ties suggest that he is more likely to deepen Abkhazia’s reliance on Moscow rather than steer it toward genuine sovereignty.

Meanwhile, Georgia has condemned the election as an illegitimate violation of its territorial integrity, and the international community remains firm in its refusal to recognize Abkhazia’s independence. The region remains caught between aspirations for sovereignty and the reality of dependence on Russia for survival. The new administration will also have to contend with growing domestic challenges, including a crippling energy crisis exacerbated by cryptocurrency mining and low water levels at a key hydroelectric plant.

As Abkhazia moves forward under Gunba’s leadership, the fundamental question remains unresolved: Can it chart an independent course free from both Georgian and Russian control, or is its political fate already sealed by its dependence on Moscow?

Abkhazia’s Historical Identity: A Nation That Predates Georgia

For most Americans, Abkhazia is little more than an obscure “separatist region” within Georgia, a mere footnote in the broader geopolitical rivalry between Russia and the West. This misleading ignores that Abkhazia is neither an artificial Soviet construct nor a newly invented breakaway republic. It is an ancient nation with a distinct ethnic, linguistic, and historical identity predating modern Georgia.

Abkhazia’s claim to independence is rooted in centuries of self-rule. Despite modern Georgian nationalist narratives, Abkhazia has never been an intrinsic part of Georgia in any meaningful sense. It has existed as an independent kingdom, a self-governing principality, and later as a republic with treaty ties to Georgia, ties which Georgia later violated. At every stage, Abkhazia’s relationship with its neighbors has been defined not by subjugation, but by a continuous assertion of autonomy.

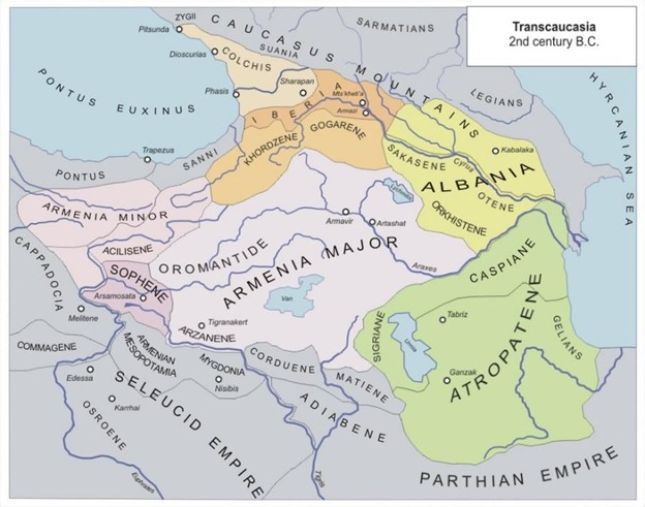

The historical record makes this clear. Abkhazia was part of the Kingdom of Colchis, a powerful civilization known in Greek mythology as the land of the Golden Fleece, where Jason and the Argonauts embarked on their legendary quest. This was not a mere myth, as Colchis was a real political entity, and the lands that later became Abkhazia were a key part of this ancient trading hub. Even in these early periods, the people inhabiting what is now Abkhazia were culturally distinct from the Kartvelian-speaking Georgians further south.

Abkhazians are not only ethnically distinct from Georgians but linguistically and genetically separate as well. The Abkhaz language belongs to the Abkhazo-Adyghean (Northwest Caucasian) family, which includes Circassian (Adyghe) and the now-extinct Ubykh language. This is entirely distinct from the Kartvelian language family, which includes Georgian, Mingrelian, and Laz. Genetic studies confirm that Abkhazians are more closely related to Circassians and Abazins than Georgians, reinforcing their status as a distinct nation.

In the medieval period, the Kingdom of Abkhazia (8th -10th century), was one of the dominant powers in the Caucasus, aligning itself with the Byzantine Empire while maintaining its own governance and language. By the 10th century, Abkhazia entered a dynastic union with the nascent Kingdom of Georgia, but this was a political alliance, not subjugation. When the Georgian kingdom fractured in the 15th century, Abkhazia reasserted its independence, forming the Principality of Abkhazia under the Chachba dynasty, which ruled for over 400 years.

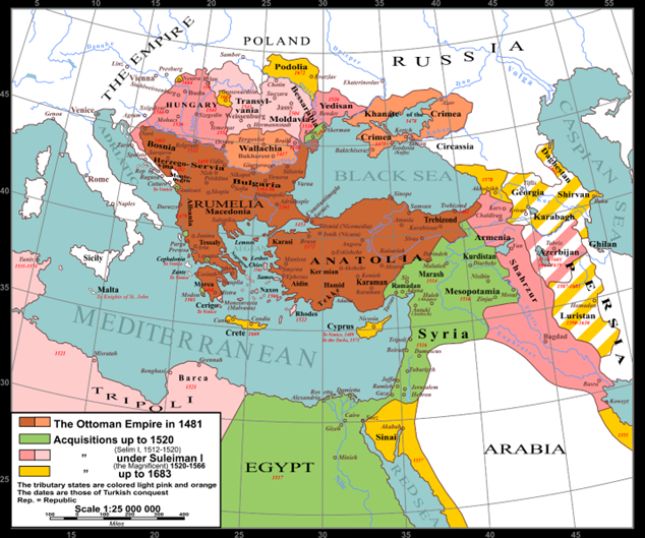

Throughout the Ottoman and Russian periods, Abkhazia skillfully balanced relations with external powers to preserve its sovereignty. The Ottoman Empire exerted influence over the Black Sea coast in the 16th and 17th centuries, with many nobles converting to Islam. Yet, Abkhazian rulers retained self-governance as an independent principality until 1810, when it became a Russian protectorate. It continued under nominal Russian suzerainty until full annexation by the Russian Empire in 1864, after which it suffered intense Russification similar to Finland and Ukraine.

Abkhazians fiercely resisted Russian rule, leading to one of the most devastating ethnic cleansings in Abkhaz history, the Muhajir deportation. More than half of the Abkhaz population was forcibly exiled to the Ottoman Empire, leading to mass displacement and the destruction of villages. Today, the Abkhaz diaspora in Turkey outnumbers the population of Abkhazia itself, reinforcing Abkhaz distrust of foreign domination, whether from Russia, Georgia, or any other power.

The Soviet Era: Abkhazia’s Forced Incorporation into Georgia

After the Russian Revolution, Abkhazia entered a union relationship with the newly independent Democratic Republic of Georgia, which quickly turned into a Georgian military occupation. When the Bolsheviks took control of the South Caucasus in 1921, they recognized Abkhazia as a full Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), equal in status to Georgia, but autonomy was short-lived, as in 1931, Stalin, himself a Georgian, forcibly incorporated Abkhazia as an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) within Soviet Georgia. This deeply unpopular move was part of a broader Soviet strategy of ethnic gerrymandering, deliberately fostering intra-Republican ethnic conflicts to prevent secessionist movements.

The “New Soviet Man” ideology claimed to unify the many nationalities of the USSR into a single Soviet identity, but in practice, the Soviet government did the opposite. By arbitrarily drawing borders, shifting populations, and promoting one ethnic group over another, Moscow ensured that nationalist aspirations would be met with internal resistance. Minority populations, like the Abkhaz in Georgia, the Karakalpaks in Uzbekistan, and the Karabakh Armenians would remain dependent on Moscow for protection in their respective republics.

In Abkhazia, Stalin and his security chief, Lavrentiy Beria, imposed a brutal Georgianization campaign to erase Abkhaz national identity. The Abkhaz language was banned in schools and replaced by mandatory Georgian-language instruction. The alphabet was forcibly converted to a Georgian-based script, further disconnecting it from its historical roots. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of ethnic Georgians were resettled in Abkhazia to shift demographics in Tbilisi’s favor.

This system ensured that when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, regions like Abkhazia were left in a state of unresolved ethnic conflict. Stalinist policies of forced integration, demographic manipulation, and cultural suppression created a deeply entrenched opposition to Georgian authority, one that would erupt into full-scale war when Georgia declared independence.

The ethnic gerrymandering did not “backfire” upon its dissolution, rather it functioned exactly as intended. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the conflicts that followed were the inevitable result of ethnic “divide and rule” strategy. Just as Ukraine saw conflict in the Donbass due to Soviet-era ethnic policies, Abkhazia’s war in 1992–1993 was the direct consequence of Moscow’s decades-long ethnic engineering, and this struggle was part of a broader pattern that played out across the former Soviet Union, from the Caucasus to Ukraine and beyond.

Abkhazia’s Struggle for Independence: War, Survival, and the Quest for Recognition

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Georgia swiftly declared independence under nationalist leader Zviad Gamsakhurdia, whose slogan “Georgia for the Georgians” rejected the autonomy of non-Georgian ethnic groups. For Abkhazia, this signaled a return to forced assimilation, reigniting long-standing fears of Georgian domination.

By 1992, tensions escalated when former Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze, who had replaced Gamsakhurdia as Georgia’s leader, sent military forces into Sukhumi to forcibly reintegrate Abkhazia. Expecting a quick victory, they instead met fierce resistance from Abkhaz fighters, many with Soviet military training. Volunteers from the North Caucasus, including Chechens and Circassians, poured into Abkhazia to join the fight, seeing it as part of a broader struggle to defend indigenous Caucasian peoples. Russia, despite its official neutrality, provided covert military support to both sides, arming Shevardnadze’s Georgia while allowing Abkhaz forces access to reinforcements from the North Caucasus.

After a year of intense fighting, the Abkhaz launched a decisive offensive in September 1993, recapturing Sukhumi and expelling the Georgian military. By the end of the month, Abkhazia had won the war, securing its de facto independence at a steep cost. Thousands were killed, much of the country’s infrastructure lay in ruins, and it found itself diplomatically isolated.

A formal ceasefire agreement was signed in Moscow in May 1994, and in November 1994, Abkhazia’s Supreme Soviet approved a new constitution, declaring full sovereignty. The constitution was ratified in a 1999 referendum, with support of 97.7% of voters.

While the war had guaranteed Abkhazia’s survival, the international community, led by the United States and the European Union, refused to recognize its independence, insisting it remained legally part of Georgia. Abkhazia was trapped in a diplomatic limbo. In practice, it functioned as an independent state, but without diplomatic recognition, it struggled to attract foreign investment or forge economic partnerships beyond Russia.

In August 2008, Georgia attempted to retake another breakaway region, South Ossetia, triggering a full-scale war with Russia. As Russian forces overwhelmed Georgia’s military, Abkhazian troops seized the opportunity to take full control of the Kodori Gorge, the last part of Abkhazia still under Georgian control.

After the war, in September 2008, Russia officially recognized Abkhazia’s independence, along with South Ossetia. After fifteen years of unrecognized sovereignty, it finally had a major international backer, but recognition came with strings attached. While Abkhazia remained nominally independent, its reliance on Moscow deepened.

Western governments denounced Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia as an illegal land grab, yet the hypocrisy was glaring. Kosovo, which unilaterally declared independence from Serbia in 2008, was recognized almost immediately by the West, despite Serbian opposition. The message was clear: self-determination was only legitimate when it aligned with Western geopolitical interests.

The Struggle for Recognition and the Road Ahead

Since 2008, Abkhazia has existed in a paradox, as a self-governing nation in every practical sense, yet diplomatically invisible to most of the world. Russia, Venezuela, Syria, Nicaragua, and Nauru recognize its sovereignty, but the overwhelming majority of countries refuse, clinging to the outdated fiction that Abkhazia is part of Georgia, even though for over three decades, Tbilisi has exercised no authority over the region. This is not a legalistic dispute, rather it is a question of accepting geopolitical reality and honoring the right to self-determination.

Abkhazia’s lack of recognition is not just a symbolic issue; it has real and severe economic and political consequences. Abkhazians cannot travel internationally with their own passports (or even with those issued by Russia), foreign investment is virtually nonexistent, and international institutions largely refuse engagement. Instead of fostering alternatives to Russian control, the West’s refusal to acknowledge Abkhazia’s independence has forced it into economic and security dependence on Moscow. By isolating Abkhazia, the West has not weakened Russia’s hold, rather it has solidified it, leaving Abkhazia with no choice but to rely on Moscow..

Abkhazia was once a thriving scientific and economic hub, with enormous untapped potential. During the Soviet era, it was not only a premier Black Sea resort but also home to world-class research institutions. The Sukhumi Primate Research Center, one of the world’s leading institutes for primatology, symbolized Abkhazia’s intellectual and scientific prominence. When I visited in 2010, it had long since fallen into disrepair, reduced to little more than a decaying zoo, a grim reflection of Abkhazia’s broader economic stagnation in the post-Soviet era. Similarly, Stalin’s dachas, once symbols of Soviet power, now stand as relics of a bygone time.

Yet, Abkhazia remains rich in natural and strategic assets; deep-water harbors, mineral resources, and a stunning coastline that once made it a major tourist destination. With access to global markets, Abkhazia could harness these strengths for real economic independence, free from both Georgian claims and Russian control. Instead, Western neglect has condemned it to reliance on Russian subsidies and black-market trade, depriving it of the tools needed to break free from economic stagnation.

Gunba’s recent election illustrates this dilemma in real time. Many Abkhazians did not vote for him out of ideological alignment with Moscow, but because they had no viable alternatives. With no access to Western financial institutions, trade partnerships, or security arrangements, deepening ties with Russia is the only path to economic survival. Ignoring Abkhazia does not strengthen Georgia’s claims but rather strengthens Russia’s grip.

Western governments claim to support self-determination, yet their inconsistencies expose their policies as more about geopolitical positioning than principle. Kosovo was recognized despite Serbia’s objections, while Abkhazia, despite meeting the same criteria, remains diplomatically isolated. The difference? In Kosovo, recognition undermined a Russian ally; in Abkhazia, it would challenge a Western one.

Reliance on outdated Soviet borders as a justification for policy is not about respecting international law, but rather about Western geopolitical strategic influence. Just as Ukraine will ultimately have to accept the loss of Crimea and Donbass, Georgia must acknowledge that Abkhazia is independent in all but name, with a population that has no desire to return to Tbilisi’s rule. By prioritizing territorial integrity over the will of the people, the West has not weakened Russia’s influence, it has reinforced it.

If the West is serious about undermining Russian dominance in the Black Sea region, it must rethink its approach. The first step is acknowledging the reality that Abkhazia is not Georgian in any meaningful sense and that forcing it under Tbilisi’s rule is neither practical nor just. This does not require immediate diplomatic recognition, but it does require breaking the cycle of isolation that pushes Abkhazia into Russia’s hands.

Instead, Western policymakers should adopt an “engagement without endorsement” strategy similar to approaches taken with Taiwan and Kosovo before their wider recognition. This means opening the door to economic partnerships, cultural exchanges, and limited diplomatic engagement. Taiwan has thrived under partial recognition, drawing in foreign investment despite its ambiguous status. Kosovo, though facing resistance from some quarters, has managed to integrate into many international markets. If Abkhazia were allowed to pursue similar opportunities, even without formal recognition, it could begin to chart an economic course independent of Moscow, reducing its reliance on Russian support.

As a concrete first step, the US and EU should establish informal diplomatic and trade offices in Sukhumi, just as they have in Taipei. Allowing Abkhazia access to international markets, development funds, and alternative security partnerships would give its leadership an alternative to total dependence on Russia. Like Taiwan and Kosovo, Abkhazia could attract investment through informal trade partnerships, providing an economic alternative to total Russian dependence. Instead of blocking Abkhazia from global markets, libertarians should push for private-sector-led economic engagement, allowing free trade to replace state-driven economic dependency.

The West’s current all-or-nothing stance guarantees the status quo, leaving Abkhazia trapped between Russian dominance and international isolation. If self-determination means anything, it must apply universally, not selectively based on geopolitical convenience. Whether in Abkhazia, Crimea, or Donbass, the will of the people must take precedence over bureaucratic legalisms designed to maintain the illusion of unity. Just as Ukraine will have to accept reality in Donbass and Crimea, Georgia must recognize that Abkhazia has been independent for over thirty years. Refusing to engage with this reality only emboldens Russia and leaves Abkhazia with no viable path forward.

The West can keep Abkhazia in diplomatic limbo for another five, ten, or twenty years, but the clock is ticking. At least when Trump joked about buying Greenland, Washington wasn’t preparing a ‘special military operation’ to make it happen. Abkhazia, however, isn’t so lucky. One day, the headlines won’t be about election fraud in Sukhumi, they’ll be about a Kremlin-backed referendum where 97.8% of voters ‘decide’ to join the Russian Federation. And when that day comes, Washington and Brussels will issue meaningless statements about ‘violations of sovereignty’ before moving on, as Abkhazia disappears into Moscow’s borders, another casualty of Western neglect.

Main photo: Border control post between Russia and Abkhazia in 2010 © by Joseph Terwilliger.

Source: AntiWar.