The US has long been a champion of “freedom of navigation”, using military force to police the world’s seaways, from the South China Sea to the Straits of Hormuz. Although the US has never ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), it consistently enforces its principles worldwide.

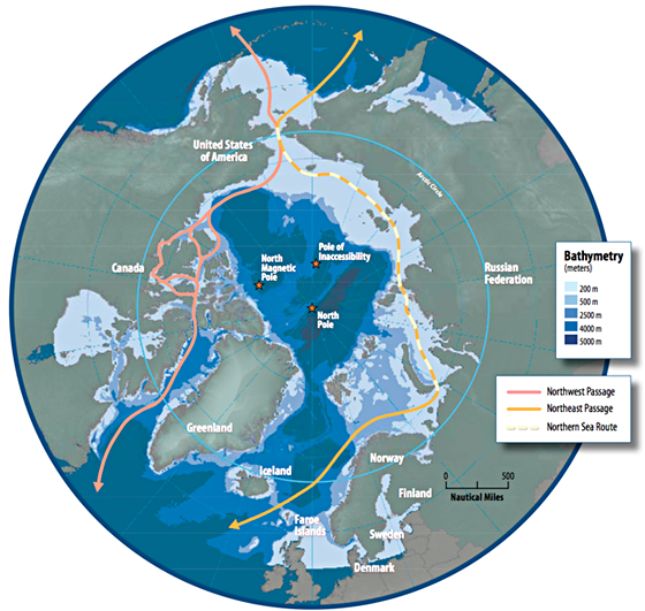

As Arctic seas ice continues to recede, opening the Northwest Passage (NWP) and the Northern Sea Route(NSR) for longer periods each year, international access to these shipping routes is becoming an ever more pressing issue, as these Arctic routes offer significantly shorter transit between Europe and East Asia than routes through the Panama or Suez canals.

Moreover, the economic and geopolitical implications of Arctic trade are staggering. Shorter and more cost-effective shipping routes will reshape the balance of global trade, and control over these routes will dictate economic flow, energy transportation, and even military positioning, given the critical role of seaborne logistics in global defense strategies. The viability of the Arctic as a major shipping region also brings with it economic opportunities in tourism, fisheries, and natural resource extraction, including oil and rare earth minerals.

Historical Context: The long quest for Arctic sea-routes

By the late Middle Ages, trade between Europe and Asia was flourishing along the Silk Road and over Portuguese-controlled shipping routes around the Cape of Good Hope. However, because such trade routes were both long and treacherous, Northern Europeans were eager to find a shorter alternative, and they believed there could be an Arctic route to get there.

For centuries, they explored the North American Arctic, looking for the NWP, a postulated sea route through the Arctic that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In 1610, Henry Hudson made it to Hudson Bay, believing he had found the NWP, but ended up trapped in ice, and died there following a mutiny. In the 19th century, John Franklin mapped large parts of the Canadian Arctic, but in 1845 he likewise got stuck in the ice and died.

Finally, in 1906, Norwegian Roald Amundsen became the first Westerner to successfully navigate the NWP in a small wooden ship, relying on survival techniques he learned from the Inuit. While he showed that the passage did in fact exist, thick ice made it commercially useless. Today, warming temperatures in the Arctic are leading to a receding of sea ice, finally unlocking the NWP, turning what was once an explorer’s graveyard into a potential global shipping route in the coming decades.

Meanwhile, Russian explorers were interested in a similar shipping route North of Siberia, the Northeast Passage (NEP), running from the Barents Sea to the Bering Strait. The first attempt to navigate the NEP came in 1648 when Semyon Dezhnev sailed through the Bering Strait, proving that Siberia was not connected to North America. His efforts were repeated in 1728 when Peter the Great sent Danish explorer Vitus Bering to confirm this information. Bering’s second expedition in 1741 landed in Alaska leading to its colonization and settlement by Russian fur traders and Orthodox missionaries.

While Dezhnev and Bering explored the coastal areas of the Russian Far East, in 1878, Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld led the first full transit of the NEP, proving Russia’s Northern coast was, in fact, navigable. Stalin’s USSR claimed full sovereignty over the NSR, building a series of Arctic bases complete with nuclear-powered icebreakers to ensure year-round access, declaring the NSR to be a historical sea route of the USSR. With the gradual warming of the Arctic, it has been hypothesized that the NSR could be ice-free all year long by 2100, making it a viable competitor to the Suez Canal for Europe-Asia shipping.

As global warming opens both NWP and NSR to global shipping, issues about freedom of navigation take center stage as both Russia and Canada claim that their respective Arctic sea-routes traverse their sovereign internal waters, giving them the right to control who goes through and under what conditions. The US disagrees and claims they should be open to ships of all nations as critical international sea lanes, based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

UNCLOS and the Legal Framework for Navigable Straits

UNCLOS was adopted in 1982 and came into force in 1994, defining different maritime zones and the rights of nations to operate in them. According to UNCLOS, territorial waters of coastal nations extend 12 nautical miles from the shoreline, over which they have complete control but must allow innocent foreign passage. Such states also have a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in which they control all resources, including oil, fishing and other resources, but foreign ships have free navigation rights. When the continental shelf extends beyond 200 nautical miles, states can further claim control over the seabed in that region (leading Canada, Denmark, and Russia to overlapping Arctic claims).

Of most concern for purposes of the NWP and NSR are two more complex defined maritime spaces, internal waters and straits used for international navigation connecting two parts of the High Seas (or EEZs).

Examples of such straits include the Bering Strait between the US and Russia, the Strait of Hormuz between Iran and Oman, and the Bosporus (entirely within Turkey but controlling access to the Black Sea). According to UNCLOS, such straits must remain open for international navigation. If the NSR and NWP are classified as international straits, connecting Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, Russia and Canada would be required to allow foreign vessels the free right to transit them.

Russia and Canada, however, consider parts of the NWP or NSR to be internal waters, over which they would have complete sovereignty and therefore claim the right to exclude any ship they like. Unfortunately, in contrast to regular contiguous coastlines, both Northern Canada and Northern Russia have many islands and archipelagos, complicating the definition of where the coastal baseline lies – this baseline is the point from which territorial waters and EEZs extend. Canada and Russia have both applied the “method of straight baselines” as defined in Section 2 Article 7 of UNCLOS, to define their internal waters, but this is controversial.

Complicating matters from the US perspective is the fact that Congress has never ratified UNCLOS, leaving the US not a full party to it, thereby weakening its legal standing to complain. Much like the International Criminal Court, despite being non-members, the US tries to hold other countries to the letter of such laws while exempting itself.

The US Approach to Freedom of Navigation: A Global Perspective

Despite not ratifying UNCLOS, the US actively defends global sea lanes to ensure open trade and shipping rights. In fiscal year 2023, for example, US forces “operationally challenged 29 excessive maritime claims advanced by 17 different claimants throughout the world,” including “straight baselines” claims of Cambodia, Colombia, China, Japan, Maldives and Vietnam.

Beyond this, the US Fifth Fleet works to ensure freedom of navigation for commercial shipping vessels around the Straits of Hormuz between Iran and Oman (through which Persian Gulf Oil exports must travel) as well as the Red Sea leading to the Suez Canal (where there have been problems with piracy and Houthi attacks in recent years). In the South China Sea, the US has repeatedly challenged Chinese claims to the so-called nine-dash-line as the boundary of their claimed territorial waters, as these claims are inconsistent with UNCLOS, claiming it had been Chinese territory since the Han Dynasty.

In the context of Freedom of Navigation (FONOPs), it is important to mention the Panama Canal. The US returned control of the Canal Zone to Panama in 1979, and control of the canal itself was returned to Panama in 1999, after a twenty-year period of transition. A treaty was signed guaranteeing the permanent neutrality of the canal such that whether at war or peace, all nations’ vessels, including those of military belligerents, had equal rights to use the canal without discrimination.

Of relevance to today’s headlines, the US agreed not to challenge Denmark’s claims to Greenland as part of a deal to purchase the Virgin Islands from them in 1917, in part to help protect access to the Panama Canal. The neutrality treaty is the basis for Marco Rubio’s recent trip to Panama to complain about increasing Chinese influence on canal operations, ostensibly as part of US efforts to guarantee freedom of the seas.

Arctic Navigation

The extent of Arctic Sea Ice is now “more than two million square kilometers less than it was in the late twentieth century,” and “reductions in the amount of Arctic sea ice that survives summer melt have resulted in more newly formed ice (first-year ice) and less of the relatively thick, old ice that makes up the perennial ice cover.” Computer models suggest that by 2060, “the oldest ice will have completely disappeared and the sea ice will reach an irreversible tipping point,” suggesting that the Arctic Ocean will be “seasonally ice-free” by the end of the 21st century, which may even allow for opening of new Trans-Arctic shipping routes that completely avoid Canadian and Russian territorial claims sometime in the next century. The changes to ice cover in the Arctic are expected to increase use of the NWP and NSR for shipping, and to open more areas of the Arctic for efficient resource extraction and export thereof.

For a variety of reasons related to ice conditions and oceanographic dynamics, the NSR is more easily navigable than the NWP. The North coast of Russia is characterized by relatively open seas, with more extreme seasonal ice melting, partly due to influences from warm Atlantic Ocean water inflows. Meanwhile in Canada, the Arctic archipelago has a complex geography with narrow channels and deep straits where thick multi-year ice persists. The archipelago also extends much farther North than the Russian coast, and the open distances between islands can be very small, creating choke points that are easily clogged with inflows of thick multiyear sea ice.

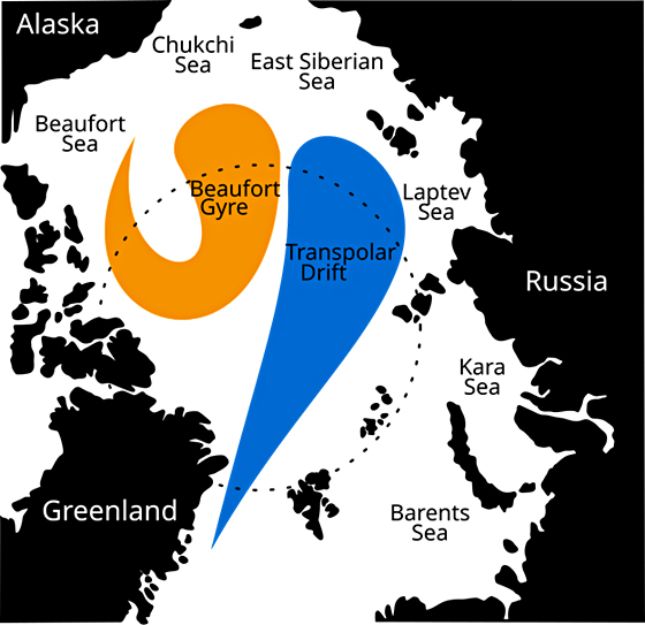

The Beaufort Gyre is a clockwise current in the Western Arctic’s Beaufort Sea, which traps multiyear sea-ice and freshwater coming from melting ice and outflow from Siberian rivers in the Canadian Arctic. The Gyre prolongs the retention of thick multi-year ice in the NWP, which is the most problematic ice for disrupting navigation.

On the other hand, the Transpolar Drift linear eastward current moves ice away from Siberia toward Greenland and the Canadian Arctic, flushing more ice into the NWP while clearing the NSR of ice.

Essentially, the Beaufort Gyre causes ice retention in the Canadian Arctic, making navigation in the Northwest Passage difficult, while the Transpolar Drift promotes ice export from the Russian Arctic, making navigation of the NSR easier.

As Arctic sea-ice melts, this effect will be more and more extreme, with the NWP becoming increasingly clogged with residual thick sea ice while the NSR becomes more and more open. Until the thick multiyear sea ice is completely gone, it is likely that despite the retreat of Arctic sea-ice, the NWP will remain obstructed and difficult to navigate reliably for the rest of the 21st century, while the NSR will be of greater and greater use as a viable year-round Arctic shipping route.

US–Canada disputes over the NWP

Canada insists that the NWP goes through their own internal waters, giving them the right to regulate traffic and exclude ships as they see fit. Canada’s claim is based on “straight baselines,” as indicated in the Territorial Sea Geographical Coordinates (Area 7) Order, and shown graphically on this map. Note that most official Canadian maps even further exaggerate their territorial extent, based on earlier pre-UNCLOS claims to even wider Arctic sovereignty.

The US counterargues that the NWP is an international strait connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and thus should be open to free international navigation.

In 1969, the SS Manhattan, an American oil tanker, was sent through the NWP without seeking permission, to test the NWP’s viability for connecting Alaskan oilfields to the US East Coast. Canada objected on the basis that an accident could cause significant pollution in their pristine Arctic lands. While not happy with the circumstances, Canada sent icebreakers to escort the vessel, realizing that such an accident would be their problem, and they had insufficient naval power to stop the US. While the trip was successful, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline proved to be a more economically viable solution given the ice conditions in the NWP.

Then, in 1985, the US Coast Guard sent the icebreaker USCGC Polar Sea through the NWP without seeking Canada’s consent. While Canada protested, there was nothing they could do about it, lacking military assets capable of deterring the Americans. As a political rather than legal solution, Canada and the US signed the 1988 Arctic Cooperation Agreement, in which the US agreed to seek Canada’s consent before future transits, and Canada agreed to approve them. The US did not, however, agree to recognize Canadian sovereignty over the NWP.

These early FONOPs were completely consistent with current US approaches to freedom of navigation, challenging the legitimacy of excessive territorial maritime claims, as it believes in freedom of navigation as a global principle. Its stance on the NWP, however, is more driven by geopolitical leverage.

By asserting navigational rights in the NWP, the US sets a precedent for similar actions demanding the Russians allow navigational rights through the NSR. However, the US did not take its dispute with Canada to international courts for two reasons. First, if Canada had won international recognition of the NWP being Canadian internal waters, Russia could use that precedent to claim full sovereignty over the NSR, denying the US and its allies access. Second, if the US had won, there would be no way to prevent Russian and Chinese ships from accessing the waters of the NWP at will. At present they honor Canada’s claim to avoid undermining their own.

US–Russia Dispute Over the NSR

While Russia does not claim the entire NSR goes through Russian internal waters, it does enforce strict control over transit, claiming that it crosses through its sovereign territory (“in particular, the Vilkitsky, Shokalsky, Sannikov and Laptev straits”), as defined by Russia’s application of “straight baselines.” Shown graphically on this map. A comparison with Canada’s claims shows they are based on effectively identical principles, which they contend are fully consistent with UNCLOS, while the US insists that as international straits they should be open to free navigation.

Russia points out that since it is impossible to transit the NSR without going through Russian internal sovereign waters because of climactic and ice conditions, Russia is allowed to establish a single navigation regime for the entire NSR.

For the right to use the NSR, significant transit fees are charged, permits are required, and Russian escorts must be allowed on every transiting ship. The current geopolitical situation, in which many countries have extensive economic sanctions against Russia, it is difficult for potential clients of the NSR to pay the fees, both for legal reasons as well as lack of access to Russian banking services. This currently restricts access to the NSR to primarily Russian and Chinese ships.

This situation has led to significant increases in FONOPs near Russian Arctic waters and therefore to a similarly increased Russian and Chinese military presence in the Arctic. Given the fact that geophysical forces are likely to increase navigability of the NSR while continuing to choke off the NWP, the US has seemingly more to gain from challenging Russian claims, though in the long term, when the NWP becomes fully navigable some decades in the future, the US has a lot to lose if their challenge is successful as such a precedent could give Russia and China reciprocal access to the NWP and the North American Arctic.

Conclusion: Trump’s Arctic Strategy

At present, the US and EU combined contribute about 22% of the roughly 37.2 billion metric tons of global CO2 emissions, and if they change nothing, by 2050 their proportion will decline to about 12% of a total of 50 billion metric tons, mostly due to increased economic activity in the Global South. If the US and EU cease all carbon emissions tomorrow, global emissions will still increase over the next two decades!

The Serenity Prayer says, “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” Is it possible that Trump’s resurgent interest in the Arctic, combined with the recent withdrawal of the US from the Paris Climate Accords are all part of the same strategic calculus? After all, while Arctic temperatures are clearly warming (whether anthropogenic or not), even a total elimination of all US carbon emissions will do nothing to alter the current trajectory.

As Arctic shipping lanes open more and more each year, Arctic natural resources like rare earth minerals and oil become more accessible, and populations gradually migrate northward over time as the climate of the planet changes, control over Arctic assets will surely become more and more important geopolitically.

Source: AntiWar.