The first third of 2023 shows a clear downward trend in freight traffic from China to the US, because American consumers are cutting back on their purchases. Is this the gentle start of a recession in the US?

The end of April 2023 marked a clear downward trend in freight traffic from China to the US. The problem is not with the Chinese suppliers, who are rapidly ramping up production. In fact, the situation is much worse: American consumers are cutting back on their purchases. Is this the gentle start of a recession in the US?

The April 2023 manufacturing PMI in the US is 47.1, noticeably lower than the "neutral" 50. This, coupled with even worse PMI data in Europe, is once again sparking a debate in the expert community about how close the US economy is to recession. Many observers are pointing in the same direction, to the possibility of a default in the US as early as June 1. However, there are other much more reliable indicators for recession today.

Maritime traffic

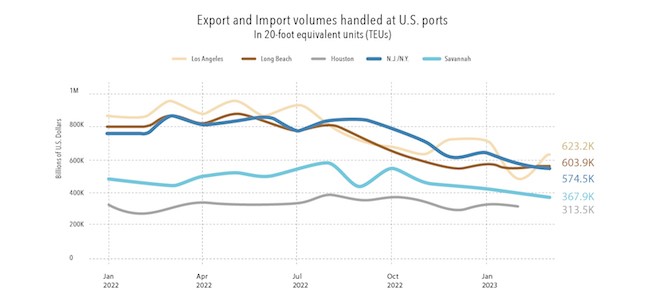

It is well known that the 2008-2009 crisis led to a 30% drop in maritime container traffic coming through a number of US ports. The same figure for 2022-2023 gives a bit of a shock: For the biggest US ports the decline is, in general, already comparable to the events of 15 years ago.

In May 2022, 967,900 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) passed through Los Angeles, the country's largest port, but in March 2023, that number was only 623,200—a drop of 35.6%. But why? It is no secret that China is the main supplier of container cargo to the US. At the end of 2022, industrial orders fell by 40% year-on-year. Adding colour to the picture is the sharp rise in inventories: New orders do not make sense if old ones cannot be sold. In other words, the picture is quite clear: a "recession in transport" being caused by a "recession in industrial orders."

Interestingly, according to feedback from logistics managers, overstocking leads to a sharp rise in inflationary pressure on their companies: Up to 48% of this pressure is attributed precisely to the cost of storing commodity surpluses.

Chart: WSJ

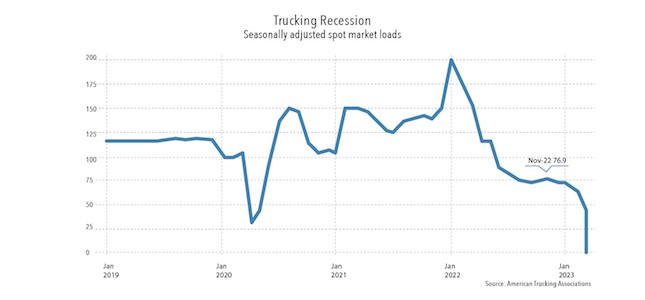

Of course, container traffic is an indirect indicator, however reliable it may be. After all, trade wars between the US and the PRC could, in theory, reduce shipments even if the US economy were doing well. A more accurate indicator is US domestic shipments, especially those that quickly reflect economic dynamics – heavy truck shipments, for instance.

And this is where the really sharp figures await us: Seasonally adjusted demand for road freight transport in the US has fallen almost to spring 2020 levels and is four times below its early 2022 peak. Even taking the 2022 average, current traffic is still 2.5 times lower than last year.

What is causing the downturn?

It is clear enough that the decline in industrial orders and overstocking is not the result of the consumer "not wanting" to spend more. De facto, they are already spending more: With inflation, real consumer spending in the US was already rising at the beginning of 2023. It is not a question of the consumer not wanting to buy new goods, but often they simply cannot afford to. Real consumer spending in the US is growing despite a decrease in the number of durable goods purchased – for example, because they now have to pay higher interest on loans, or buy houses at prices significantly higher than a couple of years ago.

If you look closely at the features of US retail sales, they point to precisely that. Firstly, retail sales have been falling for months. Secondly, their structure is important. Car dealership sales fell by 1.6% (not adjusted for inflation), furniture by 1.2%, and electronics and white goods by 2.1%. However, online shopping has risen by 1.9%, which is typical of the savings-seeking behaviour of the average person.

What is the cause of this? Is it not strange that demand is falling while GDP in the US is still growing (1.9% in the first quarter)? This is pretty clearly answered by the Fed's US money supply data: In March 2023, M2 fell by 4% year-on-year. To understand the magnitude of this event, it is worth recalling that the last time the money supply fell at such a rate was in 1933, during the Great Depression.

But there is a catch. In 1933, the US was experiencing deflation – a fall in prices. So the real money supply was shrinking more slowly than the nominal money supply. Now the US economy is experiencing rapid price growth, with a reduction in real M2 in March 2023 of 8.55% year-on-year.

So, the reasons for the demand squeeze are obvious. When the real money supply falls by more than 5%, a fall in GDP, with some lag, becomes inevitable. But why has this not happened yet? Why is there still growth?

The answer is in the same Fed data, but over a longer period of time. If you look at M2 in the US for 2020-2023, it appears to have grown by 35%. Yes, cumulative inflation has exceeded 13% over that time, but even so, the real money supply has risen considerably over three years. Does that not block the possibility of a recession?

In a normal situation, yes, most likely it would. The current money supply compression (2022-2023) is still insufficient. Because of its significant expansion in 2020, even after a one-year fall of 4%, M2 in the US is still significantly higher than at the end of 2019.

But there are significant details that make a difference. First, consumer sentiment could lead to a decline in demand even before consumers actually run out of money. Second, credit rates play a very serious role in consumer sentiment today. Most purchases of durable goods in the US are made on credit which, because of Fed action, is getting more expensive. In such an environment, a contraction in demand can start even when there is still money in the economy.

Finally, and most importantly, the US Fed still does not realise that its policy of reducing the money supply is not achieving its goals. And the Fed still wants to reduce inflation below 4% (and the official target is even a couple times lower).

How does the Fed leadership know that it has "overshot" and squeezed the money supply too severely in an attempt to suppress inflation? In fact, the Fed has only one indicator for "overcompression": the start of a recession. This combination makes the start of a recession in the second half of 2023 almost inevitable. There is very little chance of the Fed accepting high inflation at the last minute.

Could a better course of action have been taken?

At the same time, purely theoretically, a recession can still be avoided. To understand how, it is useful to look at the experience of Japan and Germany in the 1970s. Recall that both countries maintained high real interest rates in that era, which kept inflation within acceptable limits, in contrast to the US where it was much faster at the time.

But there was no reduction in M2 in Japan and Germany at that time. Why not? Of course, their central banks were not yet practising QE. They simply had to keep the exchange rate of their currencies against the dollar from getting too high, because both of these economies were deeply export-oriented in that era.

In order to maintain this exchange rate, the German and Japanese financial authorities bought dollars and gold on the foreign exchange market, replenishing their foreign exchange reserves. That meant they had to issue marks and yen, which were fed into the economy via the foreign exchange market, expanding M2. Therefore, GDP growth did not stop there, even in the face of the relatively effective suppression of inflation.

Can the US Federal Reserve repeat this strategy? Technically, of course it can. The US may not have an export surplus which could be redeemed with the dollars it issues, but it does have enormous national debt. There is nothing difficult about starting to buy it up at a serious pace while raising the discount rate to lock in inflation.

Under such conditions, American banks would sharply increase their financial strength by exchanging some of their government bond holdings for cash and could continue lending without worry. At the same time, the total amount of money in the economy would increase, eventually raising aggregate demand, albeit with a lag of a few months, as M2 changes usually work.

Will the Fed take advantage of Germany and Japan's experience from half a century ago? Not likely. History tells us that American economists always rely on their own country's experience, very rarely scrutinising the experience of others. In other words, it is very likely that a recession in the US and the Western world as a whole will still start this year.